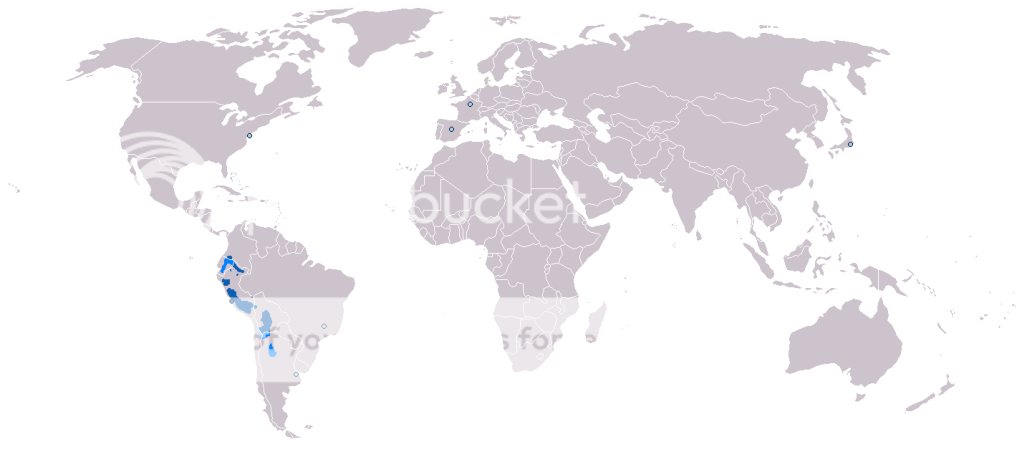

Quechua speaking Indians occupy a large portion of South America.

Quechua North American/Hebrides utility strain

Quechua Pronounced Kichwa or Kek wah depending if you describing a northern or southern dialect.

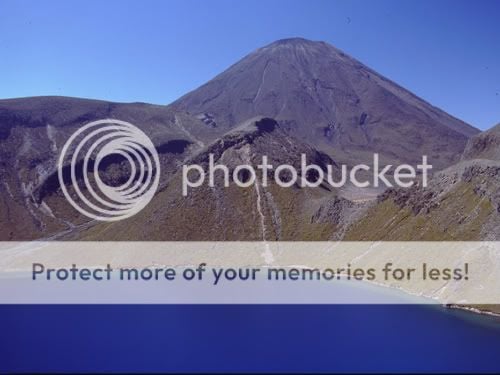

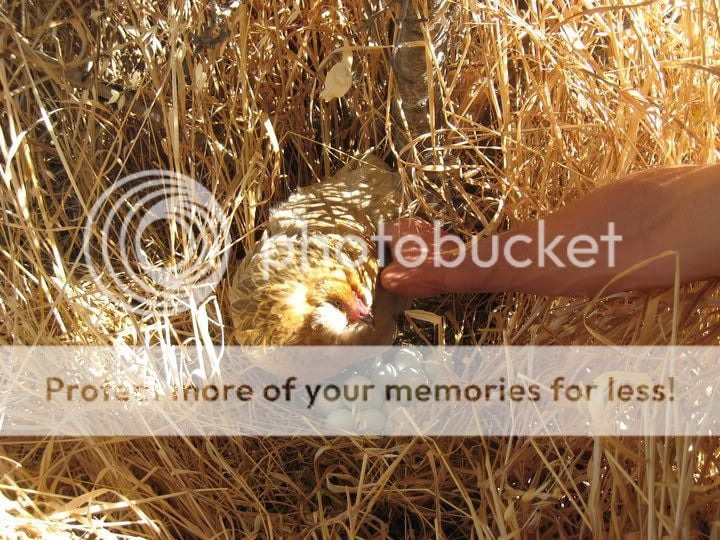

Domestic chickens known collectively as Quechua are so named because they were the primary high-altitude fowl of the Quechua speaking Indians of N. Western South America and Western Central South America.

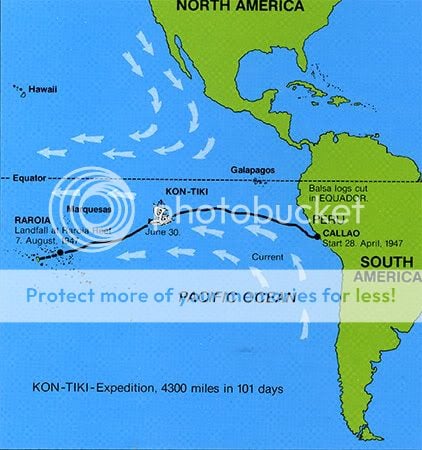

Just as sweet potatoes and red beans were carried from Quechua territory south and east to other parts of South America, so too were the Quechua fowl.

*note large multiple generation immigrant populations denoted by blue circles

The birds were considered unusually hardy and robust, long-lived and wary; a regional treasure, much as the Bresse and Marans are associated with certain regions of France. This regional refinement of poultry stock may have occurred sometime shortly after Bolivia began producing wine during the late 17th century a.d. as the birds were purportedly most common in wine producing regions. More serious trade in the regional breed probably began during the 18th and 19th centuries. This trade was primarily limited between Bolivia, Peru and Argentina. Quechua speaking Indians were and are the primary labourers of grape orchards so perhaps we can assume that some of the better stock ended up in villages interdependent with the larger wineries. Farm labourers of Quechua speaking ethnicities migrating into Argentina, Uruguay and further afield carried this important founder stock with them.

It should be made clear that Spanish and Portuguese immigrants carried domestic fowl with them when they arrived, most notably the Old Amarela.

This white egg producing, heavy bodied breed is nearly as important in the development of the Quechua as the original Quechua Indians' village hens.

This was by no means a one way genetic diffusion as Quechua stock was carried back to Portugal as well where it was used to 'improve' Portuguese, Basque and eventually even French breeds like the Faverolles. Today, sadly, the Portuguese Amarela has been improved almost to the point of extinction, its original genetics completely swamped by commercial utility breeds like the New Hampshire.

Portuguese Old Amarela rooster exhibiting traits accrued from Oceania/Quechua including colour type and winterized face.

Let me clarify something here as well. The original Quechua fowl did not produce blue or green tinted eggs. This occurred much later in the 20th century when Colloncas demes were bred to produce the first generations of the World's Fair Quechua. This is important to keep in mind in relation to the fact that the blue egg was unknown in Europe until the 1900's. More on that later.

Argentinian Quechua

Quechua Aboriginal Montane/Uruguay/ Bantam type

Quechua Tarija type

The primary point of origin of the best Quechua lines probably came from Tarija's Central Valley

Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on how you look at it, the Quechua Indians' domestic fowl was chronically perceived as needing improvement by successive generations of European migrants or those communities influenced by European culture, (as opposed to strictly loyal to aboriginal cultures). Cultural imperialism is a topic that ethnozoologists and conservationists need to educate themselved on to fully appreciate the significance of old breeds from non-European countries. When poultiers and hobbyists crow about the value of their stocks but have no comprehension of where that breed or breeds originated; nothing about the cultural history of the peoples responsible for the creation and refinement of that breed(s), ... I don't need to finish this sentence.

The original birds of the Quechua Indians were comparatively small and tended to be a bit on the wild side but they thrived where chicken yards were open to the elements and even under the constant attentions of native predators. They outlived European breeds- especially where the poultry flock could not be completely enclosed.

Increasing the size and carcass weight of the Quechua fowl were probably the first objectives of "improvement".

Improved Quechua dual purpose type- note body size and breast width

Those original Quechua fowl were essentially high altitude adapted semi-feral village fowl. The new successive generations of Quechua would be increasingly adapted for life in more or less close confinement. The introduction of chicken wire and its effect on the development of commercial utility strains is another topic altogether.

Modern Quechua photographed recently in Bolivia are largely mixed with Eurasian and North American utility breeds. Only the hen on the right resembles the original Quechua progenitive stock and even she is closer to the commercial chicken in shape and features.

Currently, since the 1950's, commercial utility breeds originating in the USA and Europe are genetically swamping the aboriginal fowl. This genetic introgression could very well lead to the extinction of the aboriginal race in South America. This is also something very likely to happen in the USA if hobbyists don't begin to take the stewardship of this cultural treasure seriously. The Ameraucana breeders have been serious about defining their gene pools for some time now but most hobbyists are not familiar with the cultural history of their favorite breed. Consequently, breeding to type and more specifically, introducing and fixing colour types common to Eurasian breeds compromises the genetic integrity of that same stock. ( A generalized point of reference, if the colour type is established in Modern Games, it probably is alien to the South American stocks and has been produced through outcrossing and subsequent selective breeding to fix that colour type.)

Nevertheless, that gene stock is closer to the original South American stock than 85% of what is available in terms of founder genetics.

Conservation of the Quechua populations in Europe and North America is of vital importance. That root stock that gave rise to the winter faced "U.K Araucana" and the winter faced "Ameraucana" was imported into our western nations at a period in time before utility breeds were brought to South America.

To be clear, the village fowl of the Quechua speaking Indians were admixtured with the Portuguese Amarela from the first. They were subsequently admixed with greater percentages of Eurasian genetics carried into South America during the early 19th century. Nevertheless, each valley inhabited by Quechua Indians has its own cultural history and there are still deep pockets of Quechua territory where Eurasian genetics are very rare or unknown. Interestingly, this is a phenomenon of the poorest and most remote villages with the least exposure to European culture.

Getting back to the early generations of 'improved' Quechua stock from regions where European cultures dominated:

There has always been some healthy portion of foreign Eurasian blood in the developed strains of the Quechua Indians' fowl. Consequently, the Quechua that eventually left Bolivia, imported into Argentina and onwards were mixed from the start. The further they were carried from their homelands, the more they were admixed with other South American races (We'll cover the Shehuen and Ona a bit later.) and also European utility breeds. In other words, taking the purist route will not lead to meaningful dialogue or conservation initiatives. Maintaining closed lines and only breeding within the appropriate gene pools will prove be entirely useful.

Getting back to the history of the Quechua:

The "improved" Quechua were carried to the Southern Eastern Coast of South America, via Argentina and Uruguay by Quechua speaking labourers from Bolivia and Argentina.

This exodus was taking place during the eastward expansion initiatives of one Samuel Lafone who is credited as being a principle architect of the agricultural economy of Uruguay and subsequently the Falklands during the mid 1800's. Dutch settlements, especially those that traded beef with Gauchos were probably the most serious poultry farmers on the islands. Sheep farming replaced cattle ranching in the Falklands at some point, I think in the late 1800's. Scottish shepherds largely replaced gauchos by the beginning of the 20th century. Quechua speaking Indians from immigrant communities in Uruguay and Argentina provided a great deal of agricultural commodities to the Falklands and consequently to seafarers of Western European descent. In other words, the Quechua Indians' contributed their poultry founder stock to the Falklands early on in the agricultural development of this important territory.

To recap, exceedingly hardy village fowl of the Quechua Indians, many of them "improved" with the genetics of Eurasian breeds were carried to Uruguay and Argentina, reaching the Falkland s during the mid 1800's. Later, during the early 1900's, Western European settlers arrived and carried with them sheep and reportedly, old hardy European breeds like the Scots Grey and Gauloise . These birds, or rather the few that managed to survive the brutal weather of the Falklands intermixed with Quechua village fowl maintained in Dutch settlements and in Scottish Shepherd crofts. The composite flocks were free ranging for many generations and consequently became their own unique Falkland Island races. Each region within the Falklands had its own unique composite naturally so we must keep that in mind when we get around to describe or try and define the U.K. Araucana and North American Bantam Ameraucanas' ancestors.

These "Falklands Hens" were much appreciated in Argentina and Uruguay as the hardiest and most desirable of all poultry breeds for a brief period.

After the first World War, the hitherto free ranging Falklands Isles hens were further refined- they were once again interbred with more thoroughly domesticated breeds to "improve" them or at least make them more useful for agricultural utilization. Argentinian poultry scientists carried them back to the South American mainland where they were interbred with Colloncas from Chile and German Langshans from Argentina. The British Faverolles very likely have Quechua progenitors ( carried to Western Europe by cargo ships in the mid 1800's) to begin with. Irregardless this old ostensibly European breed has also been mentioned as an important root stock of the greatly "improved" Quechua that would eventually be introduced to the world in its purely commercial utility form.

To recap: Falklands Quechua which were greatly admixtured with Scots Grey and Gauloise and mostly due to inclimate weather, subzero winds, predation by foxes and dogs, isolation after settlers periodically abandoned the islands- feral composites came into being. Each region within the Falklands Isles had its own unique subrace of Falklands hens. Subsequently, these Falklands hens were selectively bred back to Montane Aboriginal Quechua from Argentina and Bolivia to "fix" certain attributes of the original racial stock. The poultry scientists then interbred Colloncas; German Langshan and Faverolles into this stock to increase size and carcass quality; increase egg production and egg shell colour. These carefully selected strains became a solid, well-refined breed as popular and invaluable to Argentinian agriculture as the Rhode Island Red and Black Java became in the United States.

These greatly improved stocks of the well-established Argentinian Quechua were first introduced to the United States at the World Fair in I think the 1930's Chicago and or New York. Meanwhile, Gallus inarius the progenitor of the "Araucana" was introduced to Europe and the United States as well. In the 1960's or 70's even further refined Quechua arrived in the United States and were given the name of Easter Eggers. These original Easter Eggers were the progenitors of the North American Quechua or Ameraucana as it better known.

The Colloncas and Quetero and the Aymara are really their own races -and yes they are admixtured with the Quechua rootstock but their cultural histories are very different from that of the various Quechua breed types.

Last edited: