aliciaplus3

Free Ranging

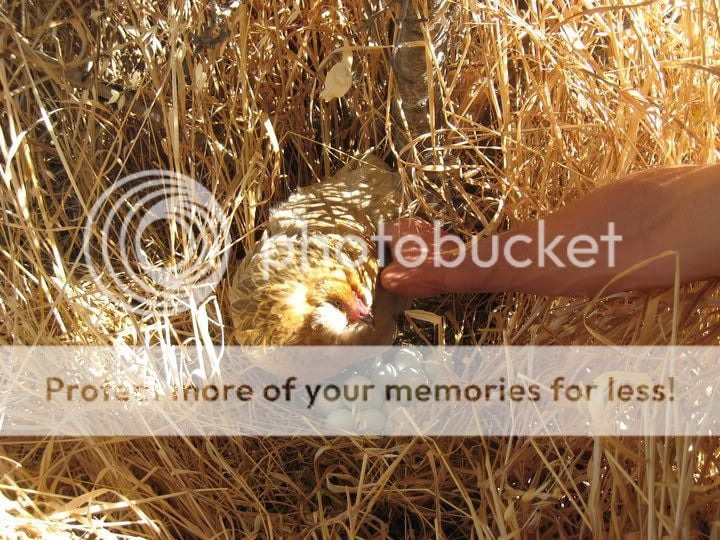

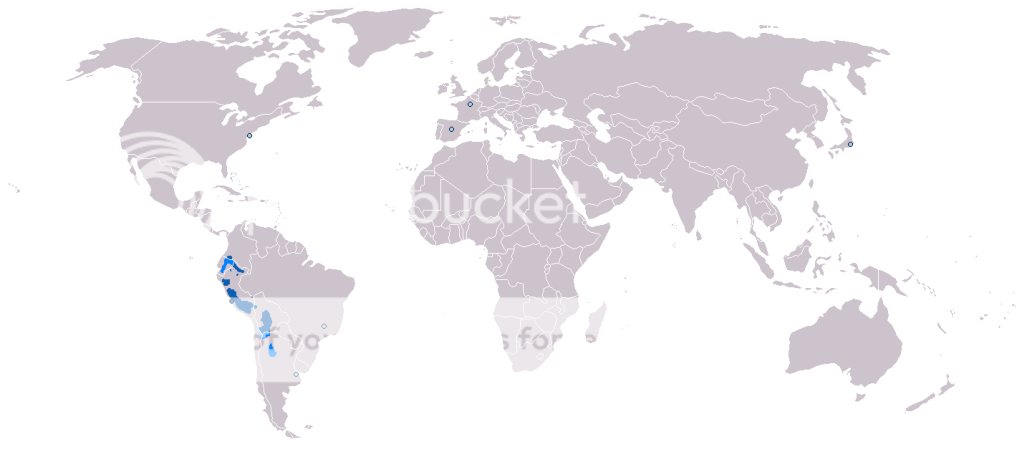

My understanding is Easter egger is a designation of s bird that has or should have the blue/green egg gene and is s mutt. They could be 2 pure breed mix or multiple generation mix match. They are sold by several hatchery's as an Americana.... aracauna.Stupid question: are easter egger just a fancy way to call hybrids of 2 pure race?

.

.