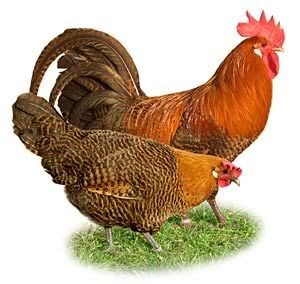

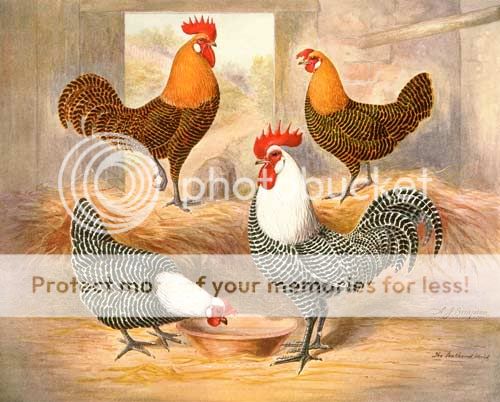

Firstly, it should be acknowledged that in ancient times, two different breed classes of chickens were treated almost as different species. The meat chickens came from China via Russia and Eastern Europe and didn't arrive in Western Europe or the Mediterranean until fairly late in history.

The races of egg producers arrived in the Mediterranean from India via the Levant and Egypt.

They did not arrive in Russia or Western Europe until about the same period in agricultural history.

Heavy-bodied, cold weather adapted Eastern races were not particularly well-suited for the lifestyle and physical environment-nutrition- the ecology that Light-bodied warm climate adapted chickens thrived in or visa vis.

The cool blooded races could almost be considered urban so intensive was their husbandry- please recall the Chinese method of hands on selective breeding and nurturing in environments mostly devoid of foraging space- the birds obliged to glean for spilled grains of rice, of barley and millet- the latter two being relatively low energy cereals. They were fed special foods but were not trusted in the confines of a garden - that was left for ducks whose feet do not damage and whose manure does not burn crops.

The warm-blooded races were more or less wild- one race (Fayoumi) considerably more so than the other (Lakenvelder). They were obliged to find most of their own food, fly larvae in the manure of feral livestock and insects in the fields. They encouraged to forage in gardens for pests and-during thrashing season, they gleaned for grains. Their diets were high in energy and the birds were obliged to wander over a wide area to procure the full benefits of their environment.

The cool blooded races were always reared and selected for utility- their meat and eggs were of vital importance.

The warm blooded races were originally kept as ceremonial creatures. They were of vital importance for sacrificial rites and good fortune. Their eggs were of growing significance and eventually the birds were maintained almost solely for their eggs.

Housing for cool blooded races was within the same structures used to shelter hoofstock from the cold or were kept within the dwellings of humans themselves.

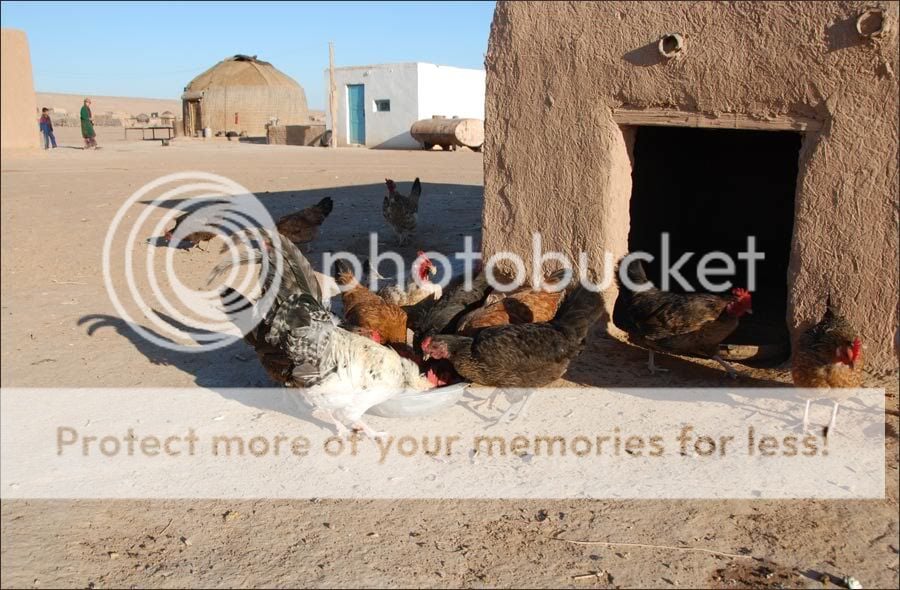

Housing for warm blooded races was non-existent, save for their adoption of certain human made structures, which gave the birds shelter, primarily from heat.

Predators of both racial groups were largely the same, though the warm blooded races had many more threats than the cool blooded.

The roots of egg farming in the Mediterranean are one of the cornerstones in the foundation of European chicken husbandry. The Mediterranean class of chickens were, until very recently in history, the world's primary egg producers.

Composites of these two racial groups are the foundation of all dual purpose commercial breeds.

A quick overview of some important breeds we can classify as "Mediterranean"

because of the period in time in which they were distributed throughout Europe . Their ancestral centres of distribution were Persia and the Red Sea respectively. The centre of dispersal for the thoroughly domesticated, egg production breeds is the Mediterranean during a period of time when cultures along the Mediterranean were experiencing their golden age (in precisely the same way that an significant percentage of uniquely Dutch/Belgium breeds came to Europe during the Dutch's astonishing exploratory -culture-building Renaissance but that actually came Indonesia, the Spice Islands, Sri Lanka, Fiji and beyond.) :

Levant:Lakenvelder

Andalusia: Andalusian

Spain: Minorca

Carthage:Friesan

Corsica:Campine

Alsace:Alsatian

Tuscany:Livorno ("Leghorn")

Catalan: Penedesencas

Sicily: Sicani ("Buttercup"/"Pheasant Fowl")

How many eggs go into one cake?

At first thought it's a no brainer. Of course eggs are an ingredient in dough- right? The question is- when was it that eggs first started being added to dough?

If we are careful to not muddle too much history- we might recall how before the

Indo-Aryans of the Levant took to mixing eggs into dough, no baked goods contained eggs. No pasta, no cake, no bread- no cookies- until the Levantine peoples ingenuously included eggs into dough, no other culture had truly discovered the greatest value of the domestic fowl.

Subsequently, Romans adopted Levantine culinary technology and with it the advent of baking came to a zenith. Imagine how much further an army could march on a diet that included protein enriched bread- and how much longer bread remained edible -thanks to the egg.

This is no small issue and the Levantine hens would be carried throughout Roman territories.

To be certain, the Phoenicians had already carried hens to their many colonies throughout the Mediterranean, but egg enriched dough was a necessity that came about only during the last gasps of the Phoenician decline, when the Levant was handed from Macedonian to Roman conquerors.

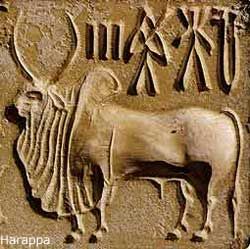

The Greeks were highly superstitious about eggs, equating the fowl with the supernatural divination of oracles. The Greeks were not that interested in eating chicken eggs. The first domestic fowl to reach Greece came from Egypt and were held in particular reverence. The second wave of chickens (Asil and the ancestor of the Dorking) came from India.

Romans followed the Greeks in many ways and means. They didn't have much of a concept of the chicken outside of its supposed oracular and spiritual -ceremonial -import. Fighting cocks was an obsession. The ruling classes certainly ate a great deal of chicken meat. Yet, until the Hebrews and other peoples from the Levant inadvertently introduced them to bread made with eggs, the ancient Romans were largely ignorant of the true value of the chicken.

Conversely, Levantine kingdoms surrounded by hostile empires, including the Romans, became increasingly dependent on sustenance farming. Combining eggs and dough was a matter ingenuity and survival. Consequently, the ever-innovative resilient Hebrews were the first peoples in all the world to culture their fowl towards superior egg production. Large white eggs produced daily by long-lived hens; cheerful roosters and the unusual phenotype, sombre, humble, bicolour these are the hallmarks of the Hebrews of post Phoenician to Roman times and refined throughout the first centuries A.D.

recap

The Mediterranean fowl was until very recently, the source of the world's primary egg production.

This came about when Romans adopted Levantine baking technology. Pasta and other egg enriched doughs became known to the entire Roman empire and onward.

This came about- the egg-enriched dough as Levantine (Phoenician) kingdoms being swallowed by Roman conquest had taken to enriching their dough with eggs as a means of storing food and ameliorating their limited food resources.

Hebrews, would take their domestic fowl from the Levant to Roman Germany- their wondrous creation the Lakenvelder came into existence almost solely to produce eggs for the new advent in baking ushered in by the Romans through the ingenuity of Jews.

Similarly, though much later in history ( circa ~ 17th century A.D.), Iberian Jews would carry their egg producing fowl to present day Belgium/Netherlands where the Brakel or Campine came into existence.

The egg enabled the what had long been a backwater in European civilization to become the Dutch empire- one of the most significant periods in human exploration and modernization in history.

The significance egg production breeds had on Western civilization cannot be overemphasized.

In order to house these birds, special enclosures had to be designed and constructed, maintained and repaired.

There was no chicken wire and the chicken "coop" had yet to come into existence.

The objective of this thread is to provide a brief overview of the history of enclosures constructed specifically for domestic fowl. In order to reach that point in our discussion, we need remind our readers that the fowl itself had to pass a certain thresh hold where it came to trust humans to begin with.

As authors just below this pass have intuited, there is a genetic basis to these important changes.

This can be summarized briefly:

The birds weren't just wild captives- they were not just being tame and doing what man wants or expects of them. The fowl is selecting habitats of humankind over those of its (many million year old) naturally designed plan. The chicken evolves with the cognitive pro-action of the human.

Before most of the Mediterranean breed class came into existence, there were just two races of domestic fowl in North Africa and the Near East. I'll organize my thoughts and attempt to describe a brief chronology of the important events leading up to the development of modern egg production breeds, which corresponds roughly with the birth of the humble hens' haus.

The simple straight to the point version is that a cote is where it all started and a logical place for innovative stewards and hobbyists to begin again- a new chapter in the day of the life of the domestic fowl...