If you go to the ALBC website and look in the download section,

http://www.albc-usa.org/EducationalResources/chickens.html

you will see the method I use. Here is a synopsis on how I do it. This is an excerpt from my article I wrote for the Plymouth Rock Club Newsletter:

To summarize I acquired stock from two breeders. During the time I acquired my Barred

Rocks, I was simultaneously involved in a breed recovery program with the

American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) involving the Buckeyes. I felt

that at the most I could manage two breeds and still hatch enough to raise to be

able to maintain a breeding flock for both. The reason I mention this is that

the ALBC has an assessment program for the Buckeyes that is very instrumental in

the culling process of any breed. Anyone can go to their website and download

the forms for use. I use that program as a basis for criteria that I look for

in my stock.

During the growing out process, you should keep your eye out for weak, deformed

and unthrifty chicks. Cull those as soon as you can, you are wanting the best

right now. I try to hatch in blocks of 20 and grow them all out together,

separating the pullets at about 8 wks. At 16 weeks I do my complete assessment

of each bird I raise. First item I do is to weigh the bird and record its

weight on my assessment sheet. I usually assess pullets first since they are

generally smaller than the cockerals. I cannot hold a bird and tell how much it

weighs, so I use put the bird in a plastic bucket sitting on a digital scale.

I then look at the head and see how large it is. Generally the heavier birds

have larger skulls meaning larger bones and an indicator of high vitality. I

then measure the heart girth, width and length of back and record those

measurements on my assessment sheet. I then take notice of how much fleshing of

breast and thighs the bird has. After all, these birds should have some meat on

those bones, at 16 wks they should be good eating size and you don't want all

bones. I like to involve anyone wanting to learn this assessment process help

me record the figures on the assessment sheet.

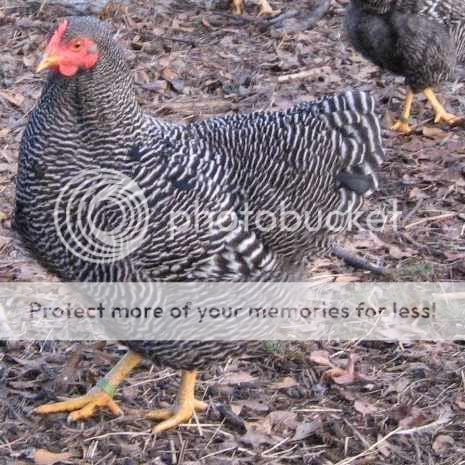

I then look at other aspects of the bird like shank size/color, points on comb and

pelvic/keel measurements. Lastly, I look at the barring on the feathers. I

rate the barring on a scale of 1-5, 5 being the best. I look at the saddle,

hackle, breast, primary and tail feathers grading each one on my sheet. If no

major defects are noted and the bird passes my benchmarks, I then tag it in a

manner that I can look at the bird in the pen walking around so I can observe

their behavior for future remarks.

This process has allowed me to select my birds in a manner that is standardized

and fair. It also allows me to immediately know which ones are the runts and do

not have good rates of growth and are culls. Several breeders I speak with also

emphasize that concentrating on the type, or shape, is priority. You can work

on color and patterns later, but that does no good if you don't have the correct

shape.

I evaluate my assessment sheet and I pick out the top 10% of each sex to band

and separate for further observation. I use weight and fleshing as the primary

criteria, and then follow there scores down in order of there evaluation. I

have found that those birds are going to be the best breeders in most scenarios.

I set my breeding pens up based on the fault I am trying to fix. The Barred

Rocks I acquired were leaps and bounds better than

any other stock I had seen, but still needed some refinement. I wanted to put

the color and fleshing on the other stock's size and rate of growth. After my

assessment the first year, I kept 1 male and 3 females from each family, keeping

the best of the best. I called one family W and the other family G based upon

who I got the original stock from. I crossed the two lines putting the male

from one family over the females of the other family. I called those "pens" G

line and W line and those names followed the females. I am sure there is a

better way to label your breeding pens, but that worked for me and you should do

what is easiest for you to remember. Keeping good records also helps to remind

you. This mating resulted in progeny of 50/50 GW. I hatched 190 chicks, as

many as I could stand, that year stirring up the gene pool greatly. This is

good and bad. First it brings every fault and good point to the surface, giving

the breeder ample opportunity to make the right choice for keepers. I saw

progeny that year every shape and size you can imagine. I will say, it made the

culling process fairly easy. If you put a bird on the scale and it weighs 1.5

lbs less than it should, you can immediately put that one in the cull pen, there

was 20 more behind it to pick from. Even if it had perfect color, its rate of

growth does not allow it to be indicative of the breed. It also allowed me the

opportunity to hold a really good bird and a really bad bird side by side, which

gave me the hands on feel of both. This tuned my senses tremendously.

The next year, I had available hens, pullets, cockerals

and roosters. This is when I cross the sons over the mothers and fathers over

daughters of both lines resulting in four breeding pens. My goal for that year

is to hatch at least 10 chicks from each of my best hens. I will then did my

selection process on these new birds and then consider all breeding stock on

there own merits. For subsequent years onward, I will mate young to old and set

up families rotating males on each family of hens. My mentor Don Shrider said

it best, "Remember, culling and selection are much more important than exactly

how the birds are mated."

Before you start breeding, you need to determine your goals for breeding. My

goal was to have good rates of growth with well fleshed birds. My secondary

goal was to get the type correct and then the coloring right. I have found that

when you get the first right, the second and third will follow. That is why I

weigh and handle my birds. I like to study photos of the birds in magazines,

internet or from shows. I also like looking in older poultry magazines for ads

of EB Thompson and other famous breeders of days gone by. I make stencils of

the profiles from these photos and paint them on the walls in the pens so I can

have side by side visuals.

I cannot say enough about how important it is to find a mentor, join a club and

read as much as you can about this subject. I would like to thank all those who

have helped me go from raising mongrels to thoroughbred stock.