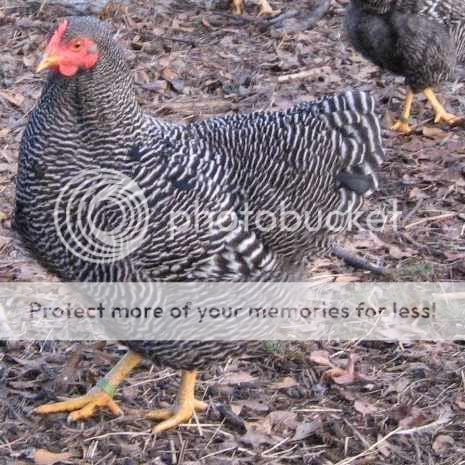

I just got an email from a person who needs Barred Rock Large Fowl females who has large fowl Cockerels. She also wants the old fashion Rhode Island Red Large Fowl and wants me to help her find a good true to breed line. It made me think how many people out there have or breed old fashion Heritage Large Fowl Chickens?

When I was a little boy growing up in South West Washington State my dad use to take us on drives every Sunday in the country. As we drove by these old farms there were signs outside these farmers fences that would show Registered Polled Herefords, Black Angus, Brown Swiss, Jersey, Holstein and Shorthorn Cattle to just name a few. When I would go to the sale barns I never saw these kinds of cattle just the normal mix match type of cattle or half Guernsey half Herford type caves.

What do you think is a Heritage Style of Poultry like the above cattle breeds I mentioned?

Do any of you have any of these rare breeds?

How many Heat age Large Fowl do you think are left in the Country during the winter months in the breeding Pens? 100 -200- 300 birds per old rare breed?

What has happen to the folks like Grand Ma who use to have a flock of nice Heritage Chickens in the 1950s?

Do you think many want to preserve these old rare breeds?

These are just a few ideas I had today as I was feeding my chickens and after I got this email from one of the members of this board. Look forward to your replies and pictures of old birds. One breed that has made major strides in the past ten years is the Buckeye folks. It proves what they have done in the past five years can be done with any old rare breed.

When I was a little boy growing up in South West Washington State my dad use to take us on drives every Sunday in the country. As we drove by these old farms there were signs outside these farmers fences that would show Registered Polled Herefords, Black Angus, Brown Swiss, Jersey, Holstein and Shorthorn Cattle to just name a few. When I would go to the sale barns I never saw these kinds of cattle just the normal mix match type of cattle or half Guernsey half Herford type caves.

What do you think is a Heritage Style of Poultry like the above cattle breeds I mentioned?

Do any of you have any of these rare breeds?

How many Heat age Large Fowl do you think are left in the Country during the winter months in the breeding Pens? 100 -200- 300 birds per old rare breed?

What has happen to the folks like Grand Ma who use to have a flock of nice Heritage Chickens in the 1950s?

Do you think many want to preserve these old rare breeds?

These are just a few ideas I had today as I was feeding my chickens and after I got this email from one of the members of this board. Look forward to your replies and pictures of old birds. One breed that has made major strides in the past ten years is the Buckeye folks. It proves what they have done in the past five years can be done with any old rare breed.

Last edited by a moderator: