The origins of domestic species is a fascinating field of interest for some.

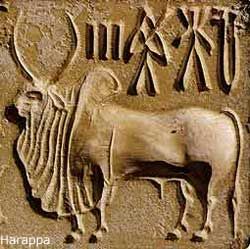

For example, where did the domestic cattle originate? What were some of the overlaying factors that led to its domestication in the first place? Why were wild cattle more successful as domestic species than say, oryx, which were also kept as captive animals by the ancients?

How were specific traits, phenotypic and/or morphological/behavioral, selected for, early on in the domestication of the species?

How many generations of close inbreeding were necessary before the prerequisite 'fixing' -of phenotypic expression- that would characterize the domesticated version- distinguish it from its wild progenitor?

In short, just where and when in the course of history did the domestic cattle (Domestic Species) emerge from its wild ancestor ( Wild Species) ?

When could domestic cattle be distinguished from wild cattle as a matter of fact and not intuition?

This integral step was necessary before cattle would become the foundation of a successful culture utilizing cattle/meat/milk/hide/etc. as its currency; providing an entire society with with staples needed for survival. Cattle culture is one of the founding developmental phases of humanity. So, it's more than just a precursory interest in cattle that leads some to investigate the origins of the domestic cattle. Its a curiosity about our own common history as human beings that leads many towards that field of interest.

Wild Species held in captivity by human beings where self-selection of mates is greatly reduced and bred in a specific direction or direction is called selective-breeding.

This is a prerequisite step in the domestication of a wild species. Once the Wild Species has been transformed by human beings into a largely human-crafted phenomenon, it has skipped the rails, so to speak. Under the supervision and maintenance of human kind, these altered lineages are moving away from the evolutionary potential of a naturally selected creature to become a Domestic Species.

Moving to a slightly different topic:

Learning about the origins of a specific Breed within that Domestic Species tends to draw an interest for a larger number of people, possibly because it draws on cultural inceptions and ingenuity. Where archaeologists are interested in the previous field of interest, many a historian will stake their tent at this subsequent step in the development of a Domestic Species.

Returning to cattle once again, in the migration of a culture characterized by its dependency on domestic cattle, we often witness evidence of the emergence of novel regional strains that differ from the original Domestic Species-often exponentially over time. These new strains may well share a common progenitor at their origin. In other words, these novel strains of the Domestic Species are generally descended of the same Domestic Ancestor. However, for any number of reasons, consequent of specific factors, some known to us and some still a mystery, Unique Regional Strains with a tendency to produce certain mutations, dark red colouration for example, would become breeds.

Over a period of many hundreds or thousands of years, a Domestic Species becomes of vital importance to a culture of people. Consequently, that culture is enabled to grow and evolve thanks to the consistence resource of protein and fats, leather and so on, provided by that domestic livestock species. This successful culture eventually migrates from its original homelands into a new region, carrying their treasured Domestic Species of livestock with them. The primitive phase of this culture's Domestic Species are, without exception, genetically homogeneous. That is to say that the flocks or herds of this primitive phase in the domestication process are, by necessity, comprised of very closely related individuals. Nevertheless, in relocating to new regions some distance away from their place of origination, these homogeneous populations tend to experience more significant genetic bottlenecks than those closer to the homeland. Perhaps the greatest reason for this is that when a flock or herd member perishes or escapes from captivity, it is not easily replaced.

This further reduces the gene pool.

So, how is a true Breed of a Domestic Species created? That's a two part question.

1. A wild species was held in captivity for unknown number of generations. Captive born progeny were select bred from, within a very small pool of genetic founders. In other words very close relatives were bred together- as a rule and- for generation after generation after generation, until a goodly percentage of unique, naturally selected genes, which would otherwise distinguish a specific evolutionary phenomenon -that is, a Wild Species- these unique genes are basically melted off- through selective breeding between close relatives. This selective breeding- the removing of layer after layer of onion skin inherited via natural selection-- it generates a genetically homogenized domestic species.

Domestic species, by and large, are not fit to survive in the natural habitats of their Wild ancestors. They may however survive and even thrive in environments alien to their ancestors. Human beings tend to create environments that are ideal for their Domestic Species. They may also introduce their primitive domestic species to islands and other environments where predators and competitors are either very rare, or absent altogether. In these situations, the Domestic Species generally reverts to a stage closer to its wild progenitors, as the animals return to a feral existence. In these situations the animals self-perpetuate, selecting their own mates and rearing their own offspring.

2. Cultures responsible for the original domestication of a given Wild Species, may or may not have refined the Domestic Species into respective strains.That is, they may have taken the Wild Species through the first primitive phases of domestication and no further. Through migration and fusion with other cultures;

Through the creation of new cultures, Unique Regional Strains emerge from the original Domestic Species. This generally requires another re assortment of genes from two or more lines of even more thoroughly homogenized founders. Again, returning to domestic cattle, three respective, very closely bred strains of Domestic Cattle are merged into a new herd. While the first few generations of intercrossing between strains dissolves genetic bottlenecks, resulting in a less genetically homogeneous Domestic Cattle herd, close inbreeding within that herd - for example, only one bull is used for two or three generations, only to be replaced by his sons, then grandsons and so on and son for decade after decade- the herd is once more comprised of extremely closely related individuals. This herd is theoretically very different in appearance and perhaps behavior from any of the parental populations. No new genes are introduced and progeny from this one herd are traded and sold over a wide region. There are no other cattle in this region. This population becomes its own breed through time and isolation, genetic drifts and selective breeding. Ecological factors may also be involved, which we will discuss later.

Domestic breeds emerged from ancient cultural diaspora and subsequent isolation.

Something that is very important to remember here, is that the vast majority of Domestic Breeds are not directly descended of a Wild Species.

Domestic Breeds are direct descendants of a Domestic Species. The Domestic Species is derived from at least one ancestral Wild Species.

This is very important to keep in mind as we move ahead into the actual crux of the discussion of the origins of the dark brown egg.

Ok, so- at this point- we've discussed the difference between a Wild species and a Domestic species. We've also covered some integral steps or phases in development- in the creation and delineation of Unique Regional Strains, which result in the eventual creation of Breeds. Now let's touch briefly on the significance of Cultural Heritage and Modern Utility Breeds respectively.

The generation of specific Cultural Heritage Breeds within a Domestic Species will hold more focus for the cultural anthropologist, for the special brand of historian most interested in their own or a specific ethnic culture. Shetland Highlander Cattle, for example, are an important Cultural Heritage Breed.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Highland Cattle is the story of their origination, where they came from and what culture is responsible for their development. I'm personally more interested in their adaptation to the Shetland Isles themselves. Their ancient ancestors were in the primitive phase of domestication- originating in Anatolia. They were carried by Phoenicians to the Celts who carried them to Scotland. Some wild European Auroch bulls contributed their genes along the way. Eventually they became their own Unique Regional Strain and eventually one of the most significant cattle Breeds.

Sustainable Agriculturists generally work with Heritage Breeds because they are more suitable for natural environments. They tend to require less management and have less of a negative impact on the land they are maintained on. They also have a story that is helpful in marketing their yield. Besides that, they tend to be more tasteful- more genuine and homey on the table than commercial breeds.

Likewise, the generation of specific Modern or Utility Breeds within a domestic species are the sole focus of many others. In fact, the field of discussion on the origins and significance of modern breeds comprises the majority of information on domestic species in general. I don't have to go into any length about the significance or development of these

major components of the global economy.

The dispersal, ownership and exhibition of Heirloom Strains of a given breed is another subject altogether.

Broadus line cattle are an heirloom strain of the Highland Cattle Heritage Breed. They are more valued by some than others but have a history unique to their lineage, and as such, hold intrinsic value and provide a specific nexus of desirable traits that breed true to type.

The Freedom Ranger broiler is a Commerical Utility Breed and one could argue that it is and was an heirloom at its inception...

I'm writing this to preface a larger discussion on the origins of the Dark Brown Egg.

It's fundamental to gain comprehension on how certain desirable attributes of a wild species-that is, certain characteristics or traits of a wild species, end up being selected for-over a long and protracted history, to eventually become the characteristic trait of a given domestic species . Case in point, the dark brown egg.

Where did it originate? Why does it matter? How can it be selected for?

To recap:

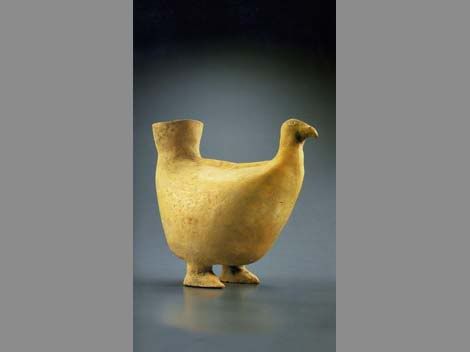

1.Wild Species: Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus

Naturally selected species inhabits native habitat.

2.Domestic Species descended of wild Red Junglefowl Progenitor Species: Domestic Fowl Gallus domesticus

* This preliminary stage/phase in domestication produces a subrace of the Wild Species that is difficult to distinguish from its wild progenitor and yet very different morphologically and behaviorally from its wild progenitor.

3.

a.Cultural Heritage Breed and Land Race descended of Domestic Fowl Progenitor Species

** this second phase in the domestication process produces distinctive strains breeds that are generally associated with a specific region of ethnic culture.

They are more genetically homogeneous than their Domestic Species progenitor and midway between fully Domestic Breed and Wild Species ancestor.

The birds in this photograph are from a closed flock living on a tiny atoll near Guam. The island has not been inhabited for over two hundred years. No new genetics have come in. These birds, nevertheless, represent the Chamorros peoples, and as such are referred to as Chamorros Fighting Games

b.and Modern Utility Breed

*** the third phase (modern utility) of the domestication process produces distinctive strains that no longer resemble their Domestic Species progenitor and are purely manmade abstractions designed for utility. The modern utility breed has no evolutionary potential to speak of and is basically a dead end so far as self-perpetuation is concerned. While some modern utility breeds can set and hatch their own eggs, the likelihood of their doing so without human beings is exceedingly low. Predators would be the first factor in preventing their natural self-perpetuation. They tend to attract predators via vocal and behavioral traits selected for in the domestication process. They also tend to make poor parents as a rule. .

4. Heirloom Strain of a given Domestic Breed :

**** the fourth phase of domestication is a bit of a grey area. Any lineage that has been carefully conserved and select bred is an heirloom. It does not necessarily need to be a rare or cultural heritage breed to be an heirloom. If there are more than eight generations of a line with no new blood added Or are the product of a master poultier ( Nancy Utterback or Bill Braden, for example) the lineage is an heirloom. Woe be the idiot that purchases this genetic material and plays Dr. Moreau with it. This is where the cavalier, short-sighted mud maker does a disservice to the focal breed and to the discipline of poultry stewardship. Many Heirloom Strains will be lineages carefully bred from excellent stock and may represent a single specific colour type.

Ok. Now we can discuss the Dark Brown Egg.

Last edited: