Sumatran Great Argus male utilising an elevated walk way in much the same manner as they might frequent natural interlocking bridges created by enormous branches between the crowns of giant trees in the primary forest. This is their preferred diurnal habitat and one in which they spend the greater percentage of their every day lives.

The Great Argus is most active on the forest floor during twilight hours. This is when the birds accomplish the most foraging, again,

while on the forest floor, as they lead a very different arboreal existence as well. During their arboreal activities ( including forays onto the highest elevations of mountain slopes within their home range) they may forage and socialize more or less actively during all hours of the day. Judging from the behaviors of captive birds, juveniles of different generations and families may well congregate there.

Subadult and juvenile Great Argus foraging together ( captive) in close cooperation. Complex social interactions between offspring of different generations are referred to as Helper Systems .

This issue is critical to understand as there are months when the Great Argus is obliged, by torrential rains, to remain in the

overstory and canopy. While in the canopy the Great Argus forages for

ants, tree frogs and their eggs , small lizards and drupes.

The management of the species in captivity is often lacking for the absence of appropriate physical space upon which the birds can frequent at different times of the day. This physical space - digression-

The ground of an aviary or zoo exhibit is landscaped and planted to create a comfortable and stimulating terrestrial habitat. Why is it that this is comforting to the birds? Because they feel that they can conceal themselves and take their leisure without worry of detection by predatory species. When something gets after an argus it retreats to the highest spot it can reach.

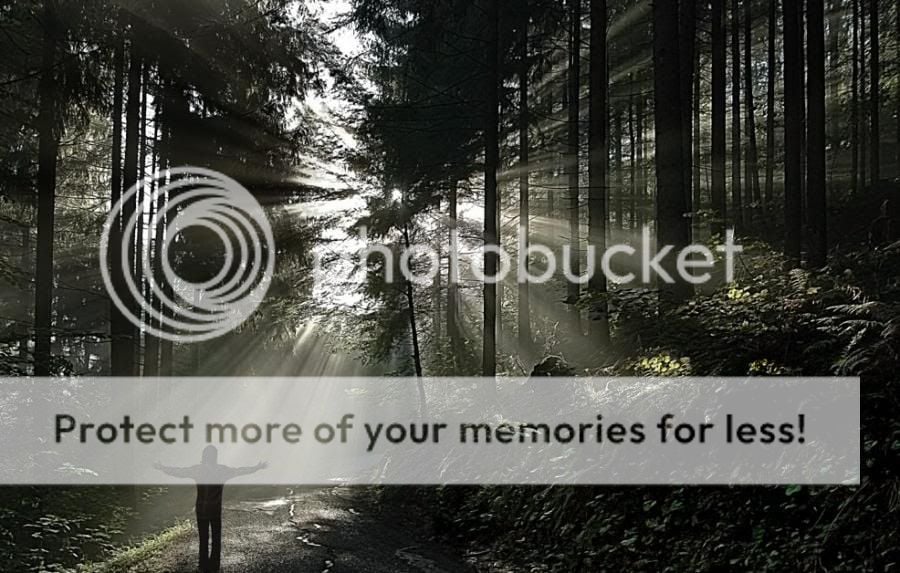

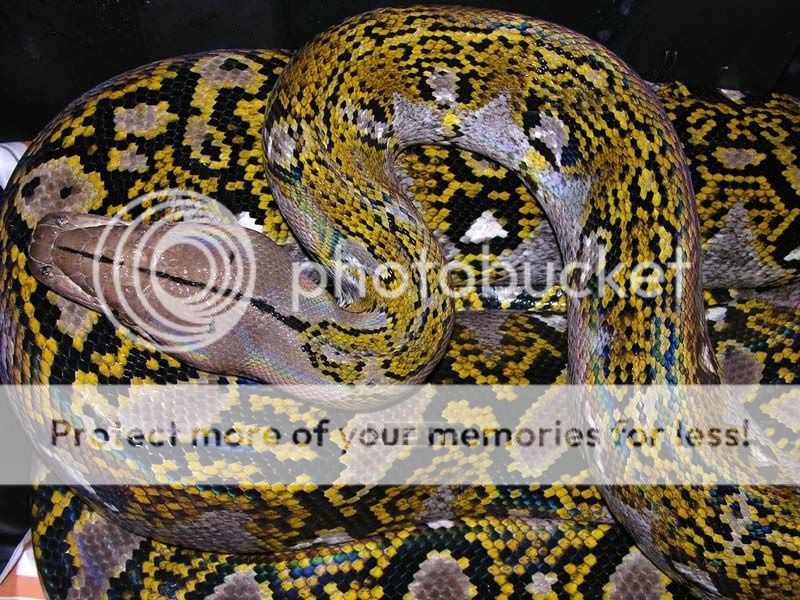

But the Argus is not truly a terrestrial species. It would prefer to spend its day on wide branches, which enable it to move about much as it might on the ground. The canopy within a primary dipterocarp forest is a bit like Swiss cheese. You can't see through it, save for a few major holes and gaps in the densest hedge of canopy but if you're a clouded leopard, a python, an orangutan or Great Argus you can move about with just as much ease as if you were on the ground. These moss covered branches are three men wide in many places and those that are growing horizontally will often interlock with one another -like covered bridges between gaps in the canopy . This is where the argus spends most of its life, an oddly terrestrial existence on the roof of the forest towering hundreds of feet above the ground.

In nature, there are two altitudes at the lowest level of the forest the Great Argus frequents, the inclined slope where it forages actively and the wide forest trails of large animals winding through the lightless understory where it forages for larger prey and paces its territory.

An argus enclosure or aviary will ostensibly be tiered at precise elevations. The mid layer loft will very often become the nesting territory where the hen will hatch her chicks and brood them for much of the day throughout their lives. You can think of this mid level loft as their main living quarters. The topmost loft is father's office and the lowest level loft is a foraging table/dining room.

The floor of the aviary becomes the yard in which the birds frequent only during certain hours of the day. Eventually, the males will take claim of the lower most loft as their soapbox arena with the front yard beneath it as their stomping territory. The flight displays of both sexes will include fluttering and hovering between lofts. The Great Argus is inactive a good deal of the day naturally but when maintained in aviaries covered in shade cloth, with shade clothed walls and shade cloth covering most of the roof of the aviary- with multiple holes cut through that shade cloth- roof- the birds become much more active as there preference is to remain invisible. Help them disappear in plain sight and they will be as active as any other peafowl.

Getting back to behavioral ecology of the Great Argus; During the dry season the Great Argus returns to its terrestrial existence on the forest floor where they forage for small animals. Chief amongst these, amphibians, ants, beetles and beetle larvae, mollusks and crustaceans, such as

small terrestrial crabs and

isopods , related to our pill bugs. They also consume fungi, decaying fruit, drupes and the shoots of certain understorey plants.

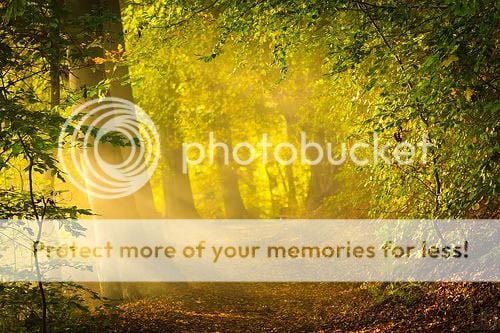

Due to the position of the sun as it relates to the canopy during daylight hours, these deep forest habitats can be nearly lightless. Indeed, naturalists have opined that

bioluminescent fungi often makes it easier to see during nightfall than during the day within virgin tropical forest.

Twilight rays course more or less horizontally and this enables crepuscular creatures to utilise their senses of sight more efficiently. The Great Argus is one of those creatures.

This bath of exquisite, particulate-rich light - that is - the air is thick in particles, forever falling from vegetation, the gossamer of spider and caterpillar silk, the pollen and spores of countless flowers, mold and fungi-the perpetual steam of transpiration- this surreal illumination reveals a dimensionless landscape unseen during other hours.

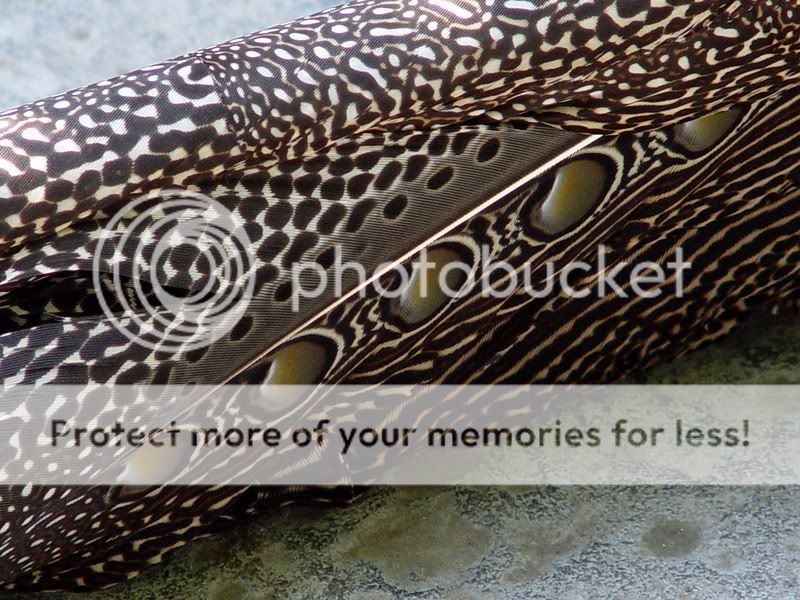

When this great python patterned, moth shaped peafowl glides hundreds of feet, sometimes hundreds of yards over the canopy -effortlessly spiraling down to its favorite terrestrial haunts, it has just a few things in mind. It must secure sufficient nutrition and keep its social unit in vocal proximity at all times.

The male of the species has also got to clear his arena of leaf litter. The arena may be as small as three yards in diameter or larger depending on the age and social ranking of the bird.

He removes every leaf, twig and stone from this clearing. This activity is his daily obsession.

This is a never-ending process as the forest if forever shedding matter. A short rain storm overnight may all but bury his clearing.

He maintains this year round in much the same manner that

Megapode males tend to their enormous mounds every day of the year regardless of their being any eggs to incubate and the manner in which male Roul Roul and

Arborphilia Hill Partridge work in concert forever repairing their curious thatched igloos built seemingly randomly about their foraging territories- in which their colony will eventually nest.

More similarly still is the manner in which male Peacock-Pheasants of the genus

Polyplectron maintain their own much smaller clearings on the forest floor replete with hollows they dig out with their bills and multiple spurs on the backs of their legs. When confronted with certain threats, the males kneel within their mini-trench they obscure their keel and breast. They vibrate their plumage against surrounding leaf litter. Within their hollow the

Polyplectron rapidly kick their legs against the earth. This sends out a vibratory signal that reptiles can readily understand.

In these instances we have male Gallomorphs modifying their environments in direct relation with territorial defense -defense of nest territory and progeny- defense of foraging territory. These birds are remarkably sedentary. They may never leave the territory in which they were born- sometimes no more than a few miles. The territorial and environment enhancing behaviors harken back to the days of the dinosaurs. These are some of the most primitive extant birds.

The colours on them are like A wow moment

The colours on them are like A wow moment