Can some one tell me some info on Egyptian Fayoumis?...........this breed really interest me, im thinking about ordering a bunch. just any info on this bird would be great thnks

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Egyptian Fayoumis info

- Thread starter jackrooster

- Start date

https://www.backyardchickens.com/breeds/fayoumis/18074 That is the only information I have been able to find here. I have always been interested in getting some and have not found anyone here who has them.

"The Egyptian Fayoumi (or simply Fayoumi, or Bigawi) is a a very old and rare breed originating from Fayoum Egypt. They were kept along the West Nile river primarily as a egg layer, and were imported to the US around the 1940s by an Iowa State University Dean of Agriculture. They are a very alert, graceful, and active breed. And are independent as well as very good foragers, though if not handled regularly they can become quite wild. They're are a fast maturing breed with cockerels crowing as early as six weeks of age and pullets laying by three and a half or four months.

They lay a medium sized white egg and are a small breed with cocks being around 4.5 pounds and hens 3.5. Hens will go broody but it may take as long as two years before they attempt though some will as soon as they begin laying. They're moderately tolerant of other birds, but they can and will be aggressive to new comers. They're hardy and are said to be very resistant to viral and bacterial infections.

They appear in a single variety: in roosters, the plumage is silver-white on the head, neck, back and saddle, with the rest in a black and white barring. Hens have heads and necks in the silver-white hue, with the rest barred. Fayoumis have a single comb, earlobes, and wattles are red and moderately large, with a white spot in the earlobes. They have dark horn colored beaks, they may have willow green or slate blue legs. Their appearance is remarkably similar to the Silver variety of the Campine breed. The neck is quite long and they have a very high tail carriage. They're not recognized by the American Poultry Association but are by the British Standards. "

Information i found/wrote for the Ultimatefowl wiki. If anyone sees anything that could be added/is wrong feel free to let me know by the way

. I tried my best to find all the info you can both in books and the net, there isn't much.

. I tried my best to find all the info you can both in books and the net, there isn't much.

-Daniel.

They lay a medium sized white egg and are a small breed with cocks being around 4.5 pounds and hens 3.5. Hens will go broody but it may take as long as two years before they attempt though some will as soon as they begin laying. They're moderately tolerant of other birds, but they can and will be aggressive to new comers. They're hardy and are said to be very resistant to viral and bacterial infections.

They appear in a single variety: in roosters, the plumage is silver-white on the head, neck, back and saddle, with the rest in a black and white barring. Hens have heads and necks in the silver-white hue, with the rest barred. Fayoumis have a single comb, earlobes, and wattles are red and moderately large, with a white spot in the earlobes. They have dark horn colored beaks, they may have willow green or slate blue legs. Their appearance is remarkably similar to the Silver variety of the Campine breed. The neck is quite long and they have a very high tail carriage. They're not recognized by the American Poultry Association but are by the British Standards. "

Information i found/wrote for the Ultimatefowl wiki. If anyone sees anything that could be added/is wrong feel free to let me know by the way

-Daniel.

Last edited:

- Dec 28, 2009

- 2,551

- 19

- 181

Yes, exactly what he said is what I am reading about them in the Storey's guide to Poultry Breeds. It says that Iowa State Univ. has had a flock since 1940, so if you are near them or contact them, I am sure they could give you more info.

Hi

Here is some information on the Egyptian Fayoumis out of a book I have '' Poultry OF THE WORLD '' by Loyl Stromberg.

Though there is no knowledge of their origin, there is one theory that the Fayoumi is the progeny of the Brakel or Campines of Belgium and were brought to Egypt by Napoleon. The second theory is that Fayoumi are the progeny of Asiatic chickens brought to Egypt by Senior Mohammed Ali Basha, President from the Anadol region of Turkey. He placed them in the Fayoum province. These chickens mixed with other native Egyptian fowl.

Long Horn Poultry Farm

Here is some information on the Egyptian Fayoumis out of a book I have '' Poultry OF THE WORLD '' by Loyl Stromberg.

Though there is no knowledge of their origin, there is one theory that the Fayoumi is the progeny of the Brakel or Campines of Belgium and were brought to Egypt by Napoleon. The second theory is that Fayoumi are the progeny of Asiatic chickens brought to Egypt by Senior Mohammed Ali Basha, President from the Anadol region of Turkey. He placed them in the Fayoum province. These chickens mixed with other native Egyptian fowl.

Long Horn Poultry Farm

I have a pair of Fayoumi's.. they are about 11 weeks now... remind me of the road runner and they are very bossy! love them

Fayoumi pullet photograph by Star Particle

http://kidsandotherpets.com/2008/05/

The Fayoumi Chicken or Bigawi , as it is known in Egypt, is one of the oldest and most enigmatic of all known chicken breeds.

It's cultural history and origination are significant because it emerged at a crossroads in ancient human civilization.

The region where this breed emerged is fascinating in of itself.

The history of domestic fowl in the Fayoum Region transects somewhat with that of an indigenous ethnic group from Upper Egypt that founded Egypt's 12th Dynasty .

The modern word used to describe the many collective tribes of this ancient people is "Bejawi", a term that has lent itself to our Fayoumi Fowl, e.g. "Bigawi".

"I shall describe what is before me,

I do not foretell what does not come:

Dry is the river of Egypt,

One crosses the water on foot;

One seeks water for ships to sail on,

Its course having turned into shoreland.

Shoreland will turn into water,

Watercourse back into shoreland.

Southwind will combat northwind,

Sky will lack the single wind.

A strange bird will breed in the Delta marsh,

Having made its nest beside the people,

The people having let it approach by default."

A passage from the The Prophecies of Neferti

1991 BCE

In order to gain a better understanding of the Bigawi Hen it is necessary to gain a solid comprehension of the region from which it came.

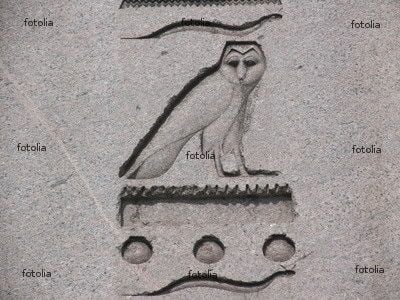

Pectoral of King Tutankhamen 1323 BCE

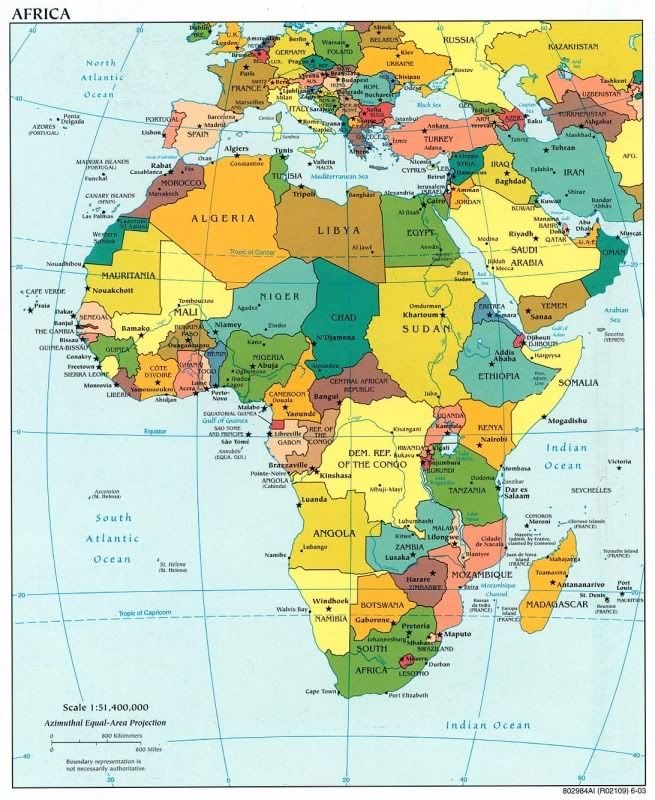

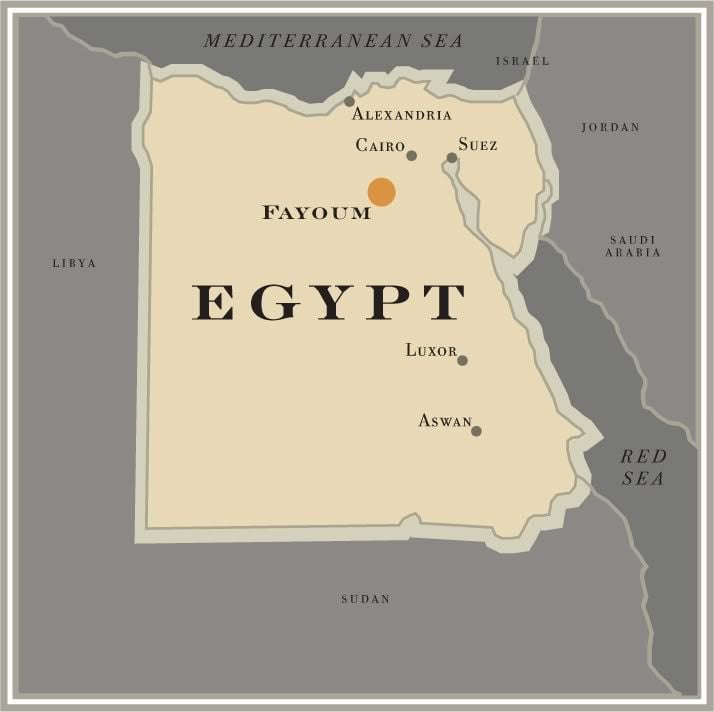

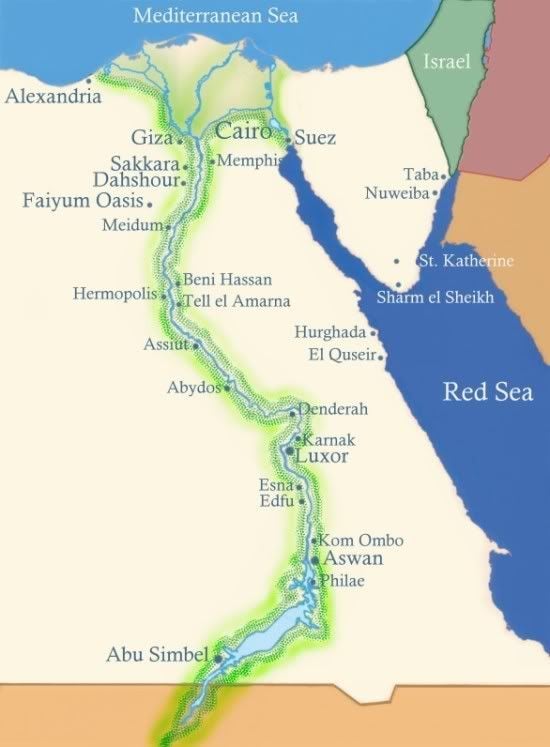

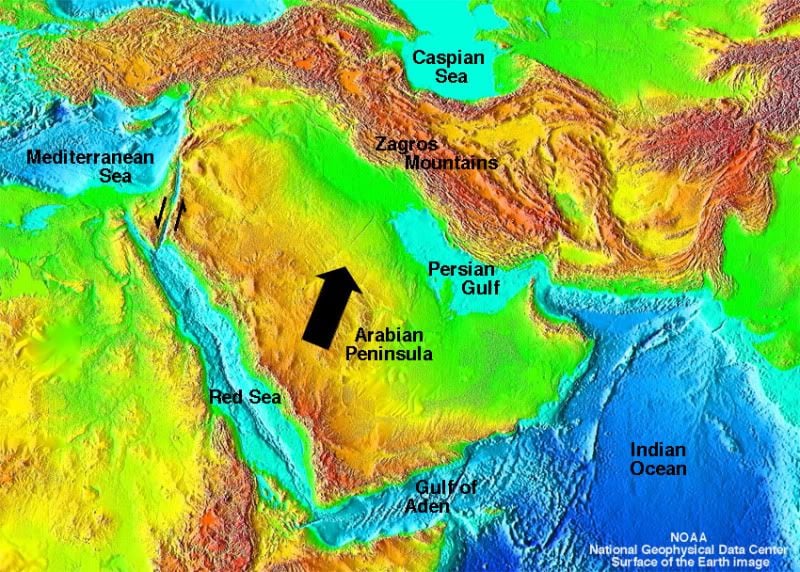

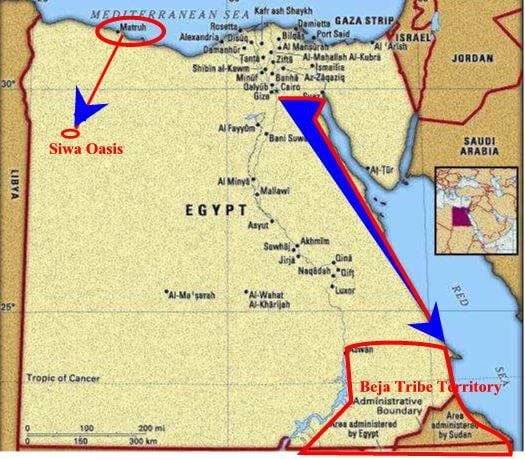

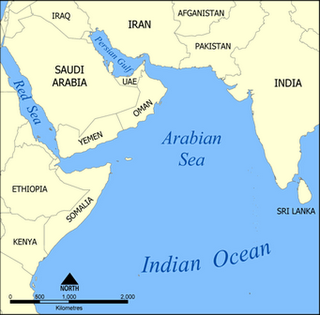

Note the location of the Fayoumi prefecture within the country of Egypt- in relation to Aswan in Upper (Southern Egypt) and the Red Sea, the shores of which border eastern Egypt, eastern Sudan, together with the Sinai (Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Syria etc.) and Arabian Peninsula

The Nile River cuts through the Eastern Portions of Egypt in the north and Sudan to the South. Both countries Easternmost boundaries abut the Red Sea

The Fayoum region is where this well known breed of domestic fowl emerged but its history is a bit more complex than its development in some currently obscure region in north east Africa. Its origins begin with the convergence of three very different cultures that were major trading partners deep in the antiquity of the ancient world.

The roots of the Fayoumi Chicken grew to life in consecutive stages from one highly significant point in history to the next and as a direct result of ancient maritime trade and more specifically, from the trade of domestic cattle and that of myrrh, frankincense, cinnamon, gold, amethyst and other semiprecious stones.

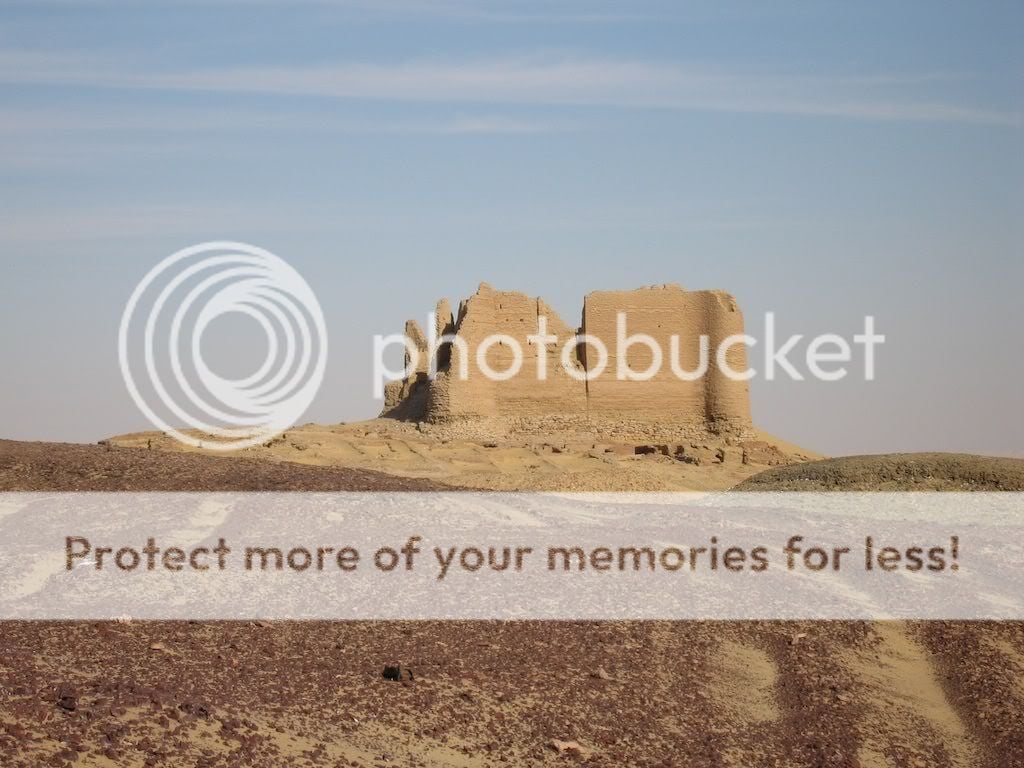

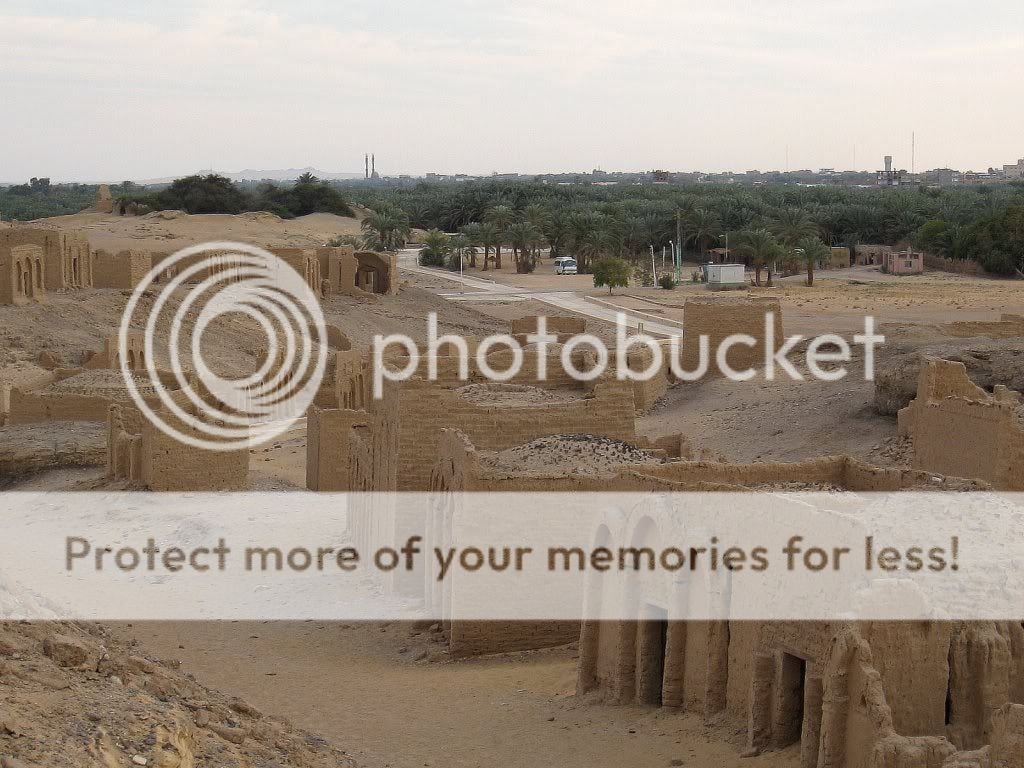

Desert overtakes the ruins of Egypt's ancient past. Water tables have shifted and humankind continues to destroy the natural ecosystem of this region .

At the very outskirts of what had been an enormous, thriving metropolis, the vegetation has been completely seared away. Sand Dunes spill over the ruins themselves.

Nevertheless, if one travels a few miles close to what had been different centres, more vestiges of once had been come into view.

Everyone reading this knows that all chickens, regardless of breed, are the descendants of wild Junglefowl, those wild cousins of the chicken, native only to South East Asia, with different, clearly defined wild species endemic to limited regions of Southern Asia and Indonesia. Because the Junglefowl is an Asian phenomenon and its domestication took place largely in Asia, it was unknown to Egypt until it was introduced to them during a specific point in history. It may have been present in Somalia and Eastern Sudan much earlier.

We will discuss the genetic composition of the specific form of primitive domestic fowl that was probably first exported from Western India and that was the primary maternal ancestor of the Fayoumi a bit later.

While that early race of fowl from Western India was essentially the same stock as that which reached Palestine, it had a very different life history -came to sometimes radically different conclusions. This is due to the consequence of very different agricultural histories of the three respective ( India; Palestine; Horn of Africa.) cultures-.

Each culture started out with the same basic genetic material of primitive domestic fowl and that genetic source material evolved differently within the agricultural centres of each of the three different cultures.

Some of this was due to the widely disparate ecological conditions of each respective civilization, which in turn have a direct relationship with the different forms of agricultural practices and nutritional supplementation that each respective culture could provide for their semi-domestic flocks.

Each of these cultures were helping to define and further domesticate the species and three very distinctive breed types emerged from this diaspora of all those many thousands of years ago.

It may well be that Junglefowl had shown up in the Egyptian court before the 18th Dynasty but as we have no record of that in archaeological record, we must assume that it did not exist in Egypt until its introduction from Palestine.

The Palestinian birds originated in India. They were in all likelihood little more than exotic curiosities that survived because they were highly adaptable and trusting of humankind. They flourished in the marshes alongside the river Nile and they were limited in number.

Because they were not raised as a domestic livestock, there was no artificial propagation of the Palestinian Hen.

The population of feral birds running wild in the ruins of Egyptian monuments in an oasis-like depression, the size of Washington D.C. - adjacent to the Nile River - yet surrounded by mountain desert- Until the late period when Greeks conquered Egypt, the population of feral chickens was probably never more than a few thousand at any given time. All these birds had descended from a much smaller number.

The origins of those founders- are described below.

It first appears in Egyptian art sometime during Egypt's 18th Dynasty ~ 14th Century BCE

The Sinai Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula

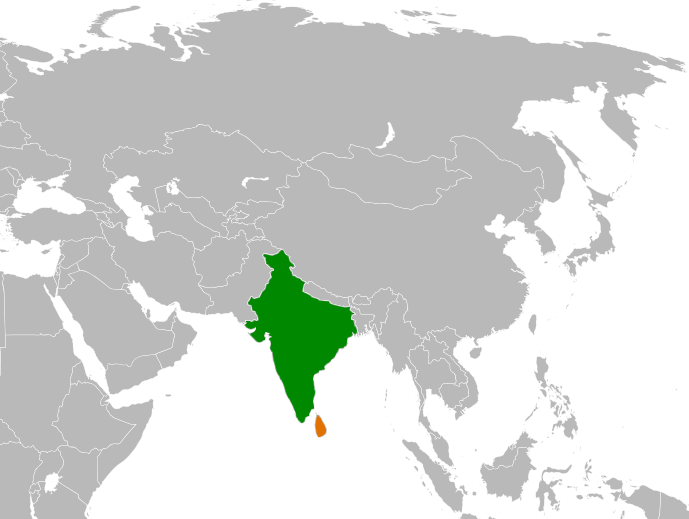

The Indian Sub-Continent (in green); Sri Lanka (in orange) in relation to the location of North East Africa (the Horn of Africa also known as Punt ; Sudan, Egypt etc.); the Sinai Peninusula and the Arabian Peninsula

I do not foretell what does not come:

Dry is the river of Egypt,

One crosses the water on foot;

One seeks water for ships to sail on,

Its course having turned into shoreland.

Shoreland will turn into water,

Watercourse back into shoreland.

Southwind will combat northwind,

Sky will lack the single wind.

A strange bird will breed in the Delta marsh,

Having made its nest beside the people,

The people having let it approach by default."

A passage from the The Prophecies of Neferti

1991 BCE

In order to gain a better understanding of the Bigawi Hen it is necessary to gain a solid comprehension of the region from which it came.

Pectoral of King Tutankhamen 1323 BCE

Note the location of the Fayoumi prefecture within the country of Egypt- in relation to Aswan in Upper (Southern Egypt) and the Red Sea, the shores of which border eastern Egypt, eastern Sudan, together with the Sinai (Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Syria etc.) and Arabian Peninsula

The Nile River cuts through the Eastern Portions of Egypt in the north and Sudan to the South. Both countries Easternmost boundaries abut the Red Sea

The Fayoum region is where this well known breed of domestic fowl emerged but its history is a bit more complex than its development in some currently obscure region in north east Africa. Its origins begin with the convergence of three very different cultures that were major trading partners deep in the antiquity of the ancient world.

The roots of the Fayoumi Chicken grew to life in consecutive stages from one highly significant point in history to the next and as a direct result of ancient maritime trade and more specifically, from the trade of domestic cattle and that of myrrh, frankincense, cinnamon, gold, amethyst and other semiprecious stones.

Desert overtakes the ruins of Egypt's ancient past. Water tables have shifted and humankind continues to destroy the natural ecosystem of this region .

At the very outskirts of what had been an enormous, thriving metropolis, the vegetation has been completely seared away. Sand Dunes spill over the ruins themselves.

Nevertheless, if one travels a few miles close to what had been different centres, more vestiges of once had been come into view.

Everyone reading this knows that all chickens, regardless of breed, are the descendants of wild Junglefowl, those wild cousins of the chicken, native only to South East Asia, with different, clearly defined wild species endemic to limited regions of Southern Asia and Indonesia. Because the Junglefowl is an Asian phenomenon and its domestication took place largely in Asia, it was unknown to Egypt until it was introduced to them during a specific point in history. It may have been present in Somalia and Eastern Sudan much earlier.

We will discuss the genetic composition of the specific form of primitive domestic fowl that was probably first exported from Western India and that was the primary maternal ancestor of the Fayoumi a bit later.

While that early race of fowl from Western India was essentially the same stock as that which reached Palestine, it had a very different life history -came to sometimes radically different conclusions. This is due to the consequence of very different agricultural histories of the three respective ( India; Palestine; Horn of Africa.) cultures-.

Each culture started out with the same basic genetic material of primitive domestic fowl and that genetic source material evolved differently within the agricultural centres of each of the three different cultures.

Some of this was due to the widely disparate ecological conditions of each respective civilization, which in turn have a direct relationship with the different forms of agricultural practices and nutritional supplementation that each respective culture could provide for their semi-domestic flocks.

Each of these cultures were helping to define and further domesticate the species and three very distinctive breed types emerged from this diaspora of all those many thousands of years ago.

It may well be that Junglefowl had shown up in the Egyptian court before the 18th Dynasty but as we have no record of that in archaeological record, we must assume that it did not exist in Egypt until its introduction from Palestine.

The Palestinian birds originated in India. They were in all likelihood little more than exotic curiosities that survived because they were highly adaptable and trusting of humankind. They flourished in the marshes alongside the river Nile and they were limited in number.

Because they were not raised as a domestic livestock, there was no artificial propagation of the Palestinian Hen.

The population of feral birds running wild in the ruins of Egyptian monuments in an oasis-like depression, the size of Washington D.C. - adjacent to the Nile River - yet surrounded by mountain desert- Until the late period when Greeks conquered Egypt, the population of feral chickens was probably never more than a few thousand at any given time. All these birds had descended from a much smaller number.

The origins of those founders- are described below.

It first appears in Egyptian art sometime during Egypt's 18th Dynasty ~ 14th Century BCE

The Sinai Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula

The Indian Sub-Continent (in green); Sri Lanka (in orange) in relation to the location of North East Africa (the Horn of Africa also known as Punt ; Sudan, Egypt etc.); the Sinai Peninusula and the Arabian Peninsula

Last edited:

The Fayoumi Chicken is an indispensable relict of this time in history for again, it was generated from the vortex of three major empires at a specific locus in history from which modern ages were eventually guild.

The oldest known expedition to Punt was organized by Pharaoh Sahu Re of the 5th dynasty (2458-2446 BC). Also around 1950 BC, in the time of King Mentuhotep III, 11th dynasty (2004-1992 BC), an officer named Hennu and three thousand men from the south transported material for building ships through Wadi Hammamat, and to Punt acquiring a number of exotic products including incense, perfume and gum was brought to Egypt.

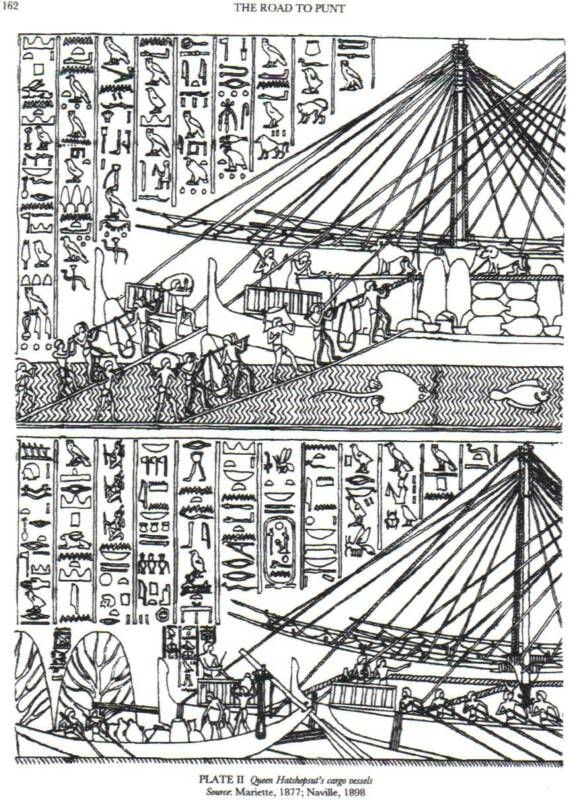

A well studied expedition was that of Queen Hatshepsut in the 18th dynasty

(1473-1458 BC). It was formed of five ships, each measuring 70 feet long, and with several sails. These accommodated 210 men, including sailors and 30 rowers, and was led by the Begawi (Beja) general "Nehsi". They departed at Quseir on the Red Sea for what was primarily a trading mission, seeking frankincense and myrrh, and fragrant unguents used for cosmetics and in religious ceremonies. However, they also brought back exotic animals and plants, ivory, silver and gold. A report of this voyage is left behind as temple reliefs in Deir el-Bahri, Egypt (see reliefs below). The reliefs shows the departure of the expedition, its arrival at the mysterious land, the landing of the ships with the gifts by the Puntine leader to Hatshepsut, and the preparations for the return voyage. The temple reliefs also showed the features of the Puntine people, who were black Africans, as well as another race the Bejawi much resembling Egyptians. Donkeys were depicted as the method of transporting goods, and white dogs guarding the peoples houses. Birds, monkeys, leopards and hippopotamus are also seen, as well as giraffes which are typical African animals, to live in Punt. The Bejawi general Nehsi is then shown in front of his tent with a banquet offered to his Puntite guests, and observing the gifts and tribute presented.

The gist of the above: Egypt, Puntland (Horn of Africa) and India were major trading partners since time immemorial. At different stages in their trading history, certain materials arrived in Egypt, which, at the time, was apparently one of the foremost epicenters of human civilization . In other words, everything worth anything eventually ended up in Egypt and it arrived through trade carried from every corner of the ancient world. Bejawi seafarers like General Nehsi traveled to Puntland, along the shores of the Northern Horn of Africa, where they converged with spice traders from India and Sri Lanka. Products from North East Africa were traded to India and Visa Versa. The Egyptians introduced Sesame to India whilst the Indians introduced Black Pepper to Egypt.

More significantly to this discussion, the ancient Egyptians were even more obsessed with immortality than modern people are. For the ancients, rare herbs and spices, gums, resins and unguents were the apothecary . The physicians of India and Egypt required massive amounts of Myrrh. Myrrh came from Punt on the Horn of Africa and a similar gum resin from Western India. Egyptian mystics and holy seers needed their Sandal Wood and this came from Southern Asia and Indonesia.

Most important of all to the ancient Egyptians, the Indians and the Puntites was Cinnamon , a spice so valuable it was worth as much as gold. Ancient peoples known in those days as the Ta-Seti and Medjay respectively , were the primary traders of the Red Sea and the deserts separating one trading empire from another. The Ta-Seti were the seafarers, moving throughout the Red Sea and surrounding coasts, whilst the Medjay traveled along the Nile River. Ta-Seti and Medjay caravans and flotillas carried Myrrh and Frankincense from Punt to Yemen and from Yemen onwards to the Indus Valley. In return, Indian sailors carried Cinnamon and Sandalwood to Ta-Seti ports in what is now eastern Sudan and northern Eritrea.

Eventually, after centuries of competition and mutual cultural exclusion, the Ta-Seti and the Medjay more or less merged into a composite trading empire known as the Ta-emDje =Baedja= Beja/ plural = Bejawi or Bigawi.

The Beja people's original homelands are in Upper Egypt, the Libyan Desert and Eastern Sudan.

Many Egyptian rulers and consequently whole dynasties were founded by Beja ethnics, for example, Amenemhet I was "born of a Ta-Seti mother, son of Upper Egypt". Ta-Seti being the name of the ancient Bejawi peoples given to them by the ancient Egyptians.

Over tens of centuries, Bejawi ethnics settled in ports from Puntland to Yemen, Oman, Western India, Orissa, Sri Lanka and Madagascar.

Last edited:

1. Hatshepsut's expedition to Punt via the Bejawi general Nehesy 1465 BCE

Ok- so we sort of covered Hatshepsut's trip to Punt on the Horn of Africa and the Bejawi (Bigawi) general/captain that led that expedition. I think most folks will be able to get the gist of the trade link. Materials from India/Sri Lanka and beyond were brought to the Horn of Africa where they were then carried by Bejawi traders into Egypt proper and into the Sinai from there. At this point in history, the Fayoum region of Egypt was still fairly verdant with a moderate population and was a large agricultural centre. However, Fayoum was no longer the capitol of Egypt. The objective of introducing Hatshepsut here is help the reader understand how valuable foreign commodities were to the ancient Egyptians and the lengths to which they were obliged to cover (literally) to procure them.

India and Egypt are a very long way from one another and Bejawi tribals controlled at least half of the trade route and extended their influence much further.

The ancestors of the Fayoumi chicken were obviously carried along that trade corridor.

2. Thutmose III's raid on Tel Meggido "Armageddon" bringing domestic Levant hens and roosters to the garden labyrinths of Fayoum in 1479 BCE

Queen Hatshepsut's younger brother Thutmose III waged a famous campaign in the Levant known as the "Battle of Meggido " from which the term "Armageddon" was coined. Amongst the spoils of war he brought back to Egypt was the hump backed Zebu cow (originally from India ) and the Canaanite domestic fowl, one that came, like the Zebu, to the Levant from India. This domestic fowl was an egg layer, and the population of fowl probably consisted of very closely related individuals that were quite a ways along in their domestication. We can assume the population was genetically homogeneous because it was described by the Egyptians as a bird that greeted the sun every morning and produced an egg every day. In other words, it was already domesticated. As this domestic fowl was carried by Indo-Aryan culture from the Indus River Civilization , it was likely that male Grey Junglefowl was an important founder of the original progenitors of the Canaanite fowl.

We can surmise as much because we know that the Grey junglefowl is native to the Indus River Valley region whilst the Red Junglefowl is not. We also know that most egg laying breeds are derived of this Indo-Aryan strain of domestic fowl and many carry the yellow skin gene unique to the Grey Junglefowl. At any rate, this is only one of the maternal progenitors of the Egyptian Fayoumi Chicken and it was carried to the Fayoum during the 18th Dynasty by King Thutmose III. He released the birds into a sacred garden where they flourished as little more than exotic curiosities within the great labyrinth. They were utilised for neither flesh nor eggs. Their vocalizations and natural tameness must surely have lent to the fondness afforded them by the Ancient Egyptians as they were never hunted out or destroyed even in such important monument of Egyptian culture.

Eventually, hard times came upon the Egyptians as a long period of drought occurred and the once tropical Fayoum basin all but dried up. The water table dropped and subsequent problems associated with stagnant pools of water, the increase in insect born diseases ie malaria, bilharzia, river blindness increased.

Salinity of surface water would also have increased. Even the religious temples would have had a rough time of it.

Fayoum was no longer the centre of Egyptian religious culture that it once was, that is, when the Ta-Seti (Bejawi) King Amenemhat moved the Egyptian Governmental Body there during the 12th Dynasty some five hundred years earlier. Consequently, after Thutmose III's death, many of the temples within Fayoum fell into ruin.

Getting back to Chickens (!), the Canaanite Tel-Megiddo chickens were left to more or less fend for themselves as we all know chickens are capable.

The religious orders still maintained temples in Fayoum and it was here that the priests responsible for giving tribute to the Nile River were permanently settled around the ever-expanding banks of Lake Moeris .

3. Subsequent cinnamon tribute from Sri Lanka including male junglefowl

Eventually, a few decades later, during the reign of King Amenhotep II, a major tribute of cinnamon from Sri Lanka was accrued from the Ta-Seti (Bejawi). Along with this cinnamon came a hundred dazzling birds intrinsically linked with the cinnamon because they were endemic to Sri Lanka. These were Ceylon Junglefowl roosters, which not incidentally, have a multiple syllabic crow that sounded to the ancient Egypts very like :"Haaypi Haaypi Herhut! Heqet! Haaypi Haaypi Herhut! Heqet!", which was the mantra river priests chanted to make the river rise:

"Haaypi Haaypi ""Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

Hail to thee, O Nile! Who manifests thyself over this land, and comes to give life to Egypt!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

Come and prosper!

Come and prosper!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

O Nile, come and prosper!

O you who make human beings to live through His flocks and His flocks through His orchards!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

Come and prosper, come,

O Nile, come and prosper!

Haaypi! Haaypi Hotep! Haaypi Hotep!"

In Ancient Egypt, failure for the river to rise was seen as a failure of the God-Kings themselves.

4. The desertification and abandonment of Fayoum

Even this tribute failed to bring the water table to its 12th Dynasty levels and Fayoum was all but abandoned. The fowl were left to fend for themselves in an environment that was being steadily encroached upon by the Egyptian desert. These hardy birds not only hung on, they flourished in the marshes amongst the reeds, foraging far out into the thorn forest during cool weather and taking shelter in the dense palm forests surrounding the ever drying lake beds.

5. Feral populations of domestic Levant stock and Sri Lanka Junglefowl sires.

The Fayoum remains basically deserted save for a few temples and larger fishing villages, agricultural regions still remained to some extent as well, but there were but a tiny fraction of human beings living in the Fayoum than had during the 12th Dynasty. A great earthquake was rumoured to have been a death knell for the labyrinth itself.

Theoretical "Tel-Megiddo Hen"

The First stage in the development of the Fayoumi Chicken was the introduction of a domestic Canaanite chickens from Tel-Megiddo ~3,479 years ago.

The second stage would be marked by the subsequent isolation for hundreds of generations of the Tel-Megiddo hen with limited founders.

A third stage would be the introduction of an unknown but likely substantial number of male Ceylon Junglefowl roughly 70 years after the initial introduction of the Tel-Megiddo Hen to temple gardens in the Fayoum Basin.

A fourth stage in the progression of this important breed was another- nearly one thousand years of isolation as a thoroughly wild species (with a uniquely skewed founder base) the Fayoum Fowl experienced subsequent to its naturalization in the Fayoum Basin.

In the beginning of their odyssey,for every female Tel-Megiddo hen there may have been an equal or slightly higher number of domestic Tel-Megiddo roosters.

After several hundred generations of close inbreeding within that small population of Tel-Megiddo Chickens, there would likely have been a rise in males, with a possibly three to one ratio- three Tel Megiddo roosters for every one hen born.

With the arrival of a shipment of Ceylon Junglefowl males seventy years later, there may have been an additional ten or even twenty roosters to every domestic Tel-Megiddo hen. The survivability and capacity to fight were probably integral for the first few years but with so many roosters minding the store, as it were, more female offspring were being produced with each generation until eventually an equilibrium was met.

Its anyone's guess how many males even survived the journey from Sri Lanka to the Horn Africa to the Nile River all the way to Fayoum, but there is no indication that a single female Ceylon Junglefowl was ever shipped.

An alliance of male Ceylon Junglefowl, note, only one male is a territory holder, the rest defer with displacement preening.

"Theoretical Second Phase Tel-Megiddo Hen" (photos courtesy of Gloria Hermontolor) after several hundred years of close inbreeding.

Theoretically speaking, the Tel-Megiddo hen was already breeding brother to sister and father to daughter before it was even carried to Fayoum as the domestic fowl was exceedingly rare in the Levant until much later times. It was considered a treasure to the Canaanites. This could have meant a slow slide into oblivion for the Tel-Megiddo hen, especially with such a wide array of native predators about the Fayoum Basin. With the introduction of so many wild Ceylon males, any genetic bottlenecks would have, and again speaking theoretically here, would certainly have put an end to any genetic bottlenecks the Fayoum population of domestic fowl may have been suffering.

Theoretical "Proto-Fayoumi Phase 1" of the Bigawi fowl (photo of Gold Campine courtesy Feathersite)

It would also have infused a whole set of new genes into the population that directly attributed to a greater survivability of the hybrid progeny.

We must also remember that the Grey Junglefowl had a very similar role in the history of the domestication of the Indus Valley chicken that was first carried to the Levant by Indo-Aryans to begin with. That is to say, one or two Grey Junglefowl roosters sired a very large number of offspring that were closely bred for many many centuries, eventually culminating in the thoroughly domesticated egg producer that was the Tel-Megiddo hen (which would subsequently become the Lakenvelder many hundreds of years later). Getting back to the purely Egyptian phenomenon, the Ceylon Junglefowl is a well-documented nest defender that enjoys an extended relationship with its offspring. It may also be a facultatively polyandrous species, or at least serially monogamous, with each female having up to three suitor/providers, which readily take up the chores of nurturing eight to twelve week chicks while she recycles another clutch. This enables the species at least two clutches a year and may well enable it to breed year round, which it has been known to in captivity in a very similar manner as bantam chickens.

Consequently, the tendency towards guilds of cooperating males competing dramatically with other all male alliances might well amount to the successful production of clutches year round, as the females would be in no short supply of day care or males in condition to breed. It may also lead to a marked precocity whereby juveniles come into sexual maturity earlier. This could also theoretically result in henny feathering.

Irregardless of those unknowable questions, the Fayoumi is markedly precocious and in instances where there are more than two roosters per hen, the entire group gets along amicably.

The Fayoumi chicken's ancestors were, for all intensive purposes, a new species, akin to an island endemic. These hybrid flocks spread throughout the Fayoum Oasis eking out a living, not as semi-domestic dung heap fowl but as wild junglefowl. They avoided humankind altogether, foraging for insects and other invertebrates in the marshes as these springs provide the only sustenance for a subtropical forest-adapted bird within the Fayoum. It should be noted however, that, the Ceylon Junglefowl actually prefers semi-arid coastal mountain habitat and is nearly absent from the rain forested interior of Sri Lanka. It may be that the considerable influence of Ceylon Junglefowl in the genetic pedigree of the Egyptian Fayoumi is what saved its progenitors from extinction. Like that wild species, the hybrids had to find food where there was very little to be found and compete with native wildlife for whatever remained. Their saving grace may have been their ability to capture flies in mid-air. One still sees them in the more remote reaches of the Fayoum wading about along canals and irrigation ditches apparently living almost entirely on flies. But that is surely an overly simplistic view of the Fayoum Fowl. As all their female ancestors could be traced back to just a few closely-related founders, selection pressures would certainly be expressed via phenotype driven by environmental conditions, such as access to water, and by predation.

Nature Reclaims the Fayoum

Irregardless of the exotic Junglefowl ancestors at the root of its heritage, the Fayoumi had a very long walk along the road of survival to succeed on before it truly came into its own existence. The every movement of these noisy foreign intruders was most assuredly watched by native predators. Species like the Pharaoh's Eagle Owl selected its prey by night, whilst the Egyptian Hawk and Sokar Falcon hunted by day. Every single bird whose plumage failed to conceal it adequately was made all the more vulnerable by that fact. The background surface of every shore and hillock is bright white and burned grey, or ochre and reddish sand, hues no Junglefowl has ever been coloured with.

Its chicks must have been even more vulnerable. Its a marvel that any exotic or foreign species of wildlife much less an ordinary chicken survived all the way into the Late Period when Greeks and Romans held dominion over Egypt and returned Fayoum into a thriving metropolis. But let's not skip ahead as those events were still a thousand years into the future give or take a few measly hundred years. In effect, the Fayoumi Fowl was on its own in the marshes of the Fayoum Basin for nearly a thousand years as a wild species. Until the Greco-Roman period there was no more mention of the domestic fowl and it was Herodotus (?) that mentioned the wild fowl living in the marshes and then, only in passing. They were impossibly wild and served no practical purpose to humankind.

It roosted then as it does now deep in the palm forest at night, which meant that it was obliged to cross wide open spaces to get there. Many of you may wonder why they didn't just stay under the palms to begin with. There is actually very little food to be found beneath palm trees, especially when they grow very closely in dense stands hundreds of acres deep. The palm forest is also home to some of their deadliest enemies. Foremost of these, the Ichneumon , or "Pharaoh's Mouse" which lived in Egypt almost exclusively on the eggs and young of crocodiles and naturally any large birds that came into its forest lair. The Ichneumon is often nocturnal hunting in packs.

The birds would forage beneath the buffalo thorn and acacia for the highly nutritious seeds of these leguminous trees where they were vulnerable to aerial attack by any one of several species of raptor. The grassland tussocks surrounding the Fayoumi Fowl's beloved marshes are home to the Egyptian Lynx, which can jump many yards into the air to capture not just one but two or even three pigeons in one assault. Then there's the Golden Jackal known to snatch prey from the mouths of lions...

Bigawi (Old Egyptian)

Shakshuk

Modern Fayoumi

Dandarawi

There is a whole history of the Fayoumi Fowl that begins a full thousand years after its isolation as a wild bird in the Fayoum Basin.

This is during Greco-Roman times when additional domestic fowl were carried into Egypt from Syria and Persia. These birds were likely very closely related if not identical to the original Tel-Megiddo hen. These tame domestic birds came to live amongst the human settlements along the banks of the lakes of Fayoum. Naturally, this invited the attentions of the wild Bigawi fowl, which interbred freely with their humanized cousins. The modern day Fayoumi Chicken that one buys in hatcheries is generally a descendant of this ancient composite.

There are however, at least three different breeds of Egyptian chickens that deserve mentioning.

The Bigawi is differentiated from the Modern Fayoumi by size, colour and temperament. The Bigawi is a bit smaller and battier than the Fayoumi. Females are a rich chestnut brown with bold black transverse barring. Males are difficult to discern from Modern Fayoumi , though they tend to be darker in the wings with darker and longer tails as well. Both Bigawi and Modern Fayoumi should have dark facial skin and an unusual crow that is easily distinguishable from any other breed of rooster.

The Shakshuk Fayoumi is the common strain of unimproved Fayoumi that one sees in villages throughout the Fayoum and in the cemetery of Old Cairo. They are brightly coloured with vivid yellow legs and ginger hued feathers.

The Dandarawi is of very recent origins created in an agricultural university in Assiut. This breed is analogous with our dual purpose utility breeds. It is a composite of different old African breeds like the Malagasy and European breeds such as the Braekel. A good deal of its genetics come from the Fayoumi fowl as well.

Hail to thee, O Nile! Who manifests thyself over this land, and comes to give life to Egypt!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

Come and prosper!

Come and prosper!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

O Nile, come and prosper!

O you who make human beings to live through His flocks and His flocks through His orchards!

"Herhut! Heqet! Herhut! Heqet!"

Come and prosper, come,

O Nile, come and prosper!

Haaypi! Haaypi Hotep! Haaypi Hotep!"

In Ancient Egypt, failure for the river to rise was seen as a failure of the God-Kings themselves.

4. The desertification and abandonment of Fayoum

Even this tribute failed to bring the water table to its 12th Dynasty levels and Fayoum was all but abandoned. The fowl were left to fend for themselves in an environment that was being steadily encroached upon by the Egyptian desert. These hardy birds not only hung on, they flourished in the marshes amongst the reeds, foraging far out into the thorn forest during cool weather and taking shelter in the dense palm forests surrounding the ever drying lake beds.

5. Feral populations of domestic Levant stock and Sri Lanka Junglefowl sires.

The Fayoum remains basically deserted save for a few temples and larger fishing villages, agricultural regions still remained to some extent as well, but there were but a tiny fraction of human beings living in the Fayoum than had during the 12th Dynasty. A great earthquake was rumoured to have been a death knell for the labyrinth itself.

Theoretical "Tel-Megiddo Hen"

The First stage in the development of the Fayoumi Chicken was the introduction of a domestic Canaanite chickens from Tel-Megiddo ~3,479 years ago.

The second stage would be marked by the subsequent isolation for hundreds of generations of the Tel-Megiddo hen with limited founders.

A third stage would be the introduction of an unknown but likely substantial number of male Ceylon Junglefowl roughly 70 years after the initial introduction of the Tel-Megiddo Hen to temple gardens in the Fayoum Basin.

A fourth stage in the progression of this important breed was another- nearly one thousand years of isolation as a thoroughly wild species (with a uniquely skewed founder base) the Fayoum Fowl experienced subsequent to its naturalization in the Fayoum Basin.

In the beginning of their odyssey,for every female Tel-Megiddo hen there may have been an equal or slightly higher number of domestic Tel-Megiddo roosters.

After several hundred generations of close inbreeding within that small population of Tel-Megiddo Chickens, there would likely have been a rise in males, with a possibly three to one ratio- three Tel Megiddo roosters for every one hen born.

With the arrival of a shipment of Ceylon Junglefowl males seventy years later, there may have been an additional ten or even twenty roosters to every domestic Tel-Megiddo hen. The survivability and capacity to fight were probably integral for the first few years but with so many roosters minding the store, as it were, more female offspring were being produced with each generation until eventually an equilibrium was met.

Its anyone's guess how many males even survived the journey from Sri Lanka to the Horn Africa to the Nile River all the way to Fayoum, but there is no indication that a single female Ceylon Junglefowl was ever shipped.

An alliance of male Ceylon Junglefowl, note, only one male is a territory holder, the rest defer with displacement preening.

"Theoretical Second Phase Tel-Megiddo Hen" (photos courtesy of Gloria Hermontolor) after several hundred years of close inbreeding.

Theoretically speaking, the Tel-Megiddo hen was already breeding brother to sister and father to daughter before it was even carried to Fayoum as the domestic fowl was exceedingly rare in the Levant until much later times. It was considered a treasure to the Canaanites. This could have meant a slow slide into oblivion for the Tel-Megiddo hen, especially with such a wide array of native predators about the Fayoum Basin. With the introduction of so many wild Ceylon males, any genetic bottlenecks would have, and again speaking theoretically here, would certainly have put an end to any genetic bottlenecks the Fayoum population of domestic fowl may have been suffering.

Theoretical "Proto-Fayoumi Phase 1" of the Bigawi fowl (photo of Gold Campine courtesy Feathersite)

It would also have infused a whole set of new genes into the population that directly attributed to a greater survivability of the hybrid progeny.

We must also remember that the Grey Junglefowl had a very similar role in the history of the domestication of the Indus Valley chicken that was first carried to the Levant by Indo-Aryans to begin with. That is to say, one or two Grey Junglefowl roosters sired a very large number of offspring that were closely bred for many many centuries, eventually culminating in the thoroughly domesticated egg producer that was the Tel-Megiddo hen (which would subsequently become the Lakenvelder many hundreds of years later). Getting back to the purely Egyptian phenomenon, the Ceylon Junglefowl is a well-documented nest defender that enjoys an extended relationship with its offspring. It may also be a facultatively polyandrous species, or at least serially monogamous, with each female having up to three suitor/providers, which readily take up the chores of nurturing eight to twelve week chicks while she recycles another clutch. This enables the species at least two clutches a year and may well enable it to breed year round, which it has been known to in captivity in a very similar manner as bantam chickens.

Consequently, the tendency towards guilds of cooperating males competing dramatically with other all male alliances might well amount to the successful production of clutches year round, as the females would be in no short supply of day care or males in condition to breed. It may also lead to a marked precocity whereby juveniles come into sexual maturity earlier. This could also theoretically result in henny feathering.

Irregardless of those unknowable questions, the Fayoumi is markedly precocious and in instances where there are more than two roosters per hen, the entire group gets along amicably.

The Fayoumi chicken's ancestors were, for all intensive purposes, a new species, akin to an island endemic. These hybrid flocks spread throughout the Fayoum Oasis eking out a living, not as semi-domestic dung heap fowl but as wild junglefowl. They avoided humankind altogether, foraging for insects and other invertebrates in the marshes as these springs provide the only sustenance for a subtropical forest-adapted bird within the Fayoum. It should be noted however, that, the Ceylon Junglefowl actually prefers semi-arid coastal mountain habitat and is nearly absent from the rain forested interior of Sri Lanka. It may be that the considerable influence of Ceylon Junglefowl in the genetic pedigree of the Egyptian Fayoumi is what saved its progenitors from extinction. Like that wild species, the hybrids had to find food where there was very little to be found and compete with native wildlife for whatever remained. Their saving grace may have been their ability to capture flies in mid-air. One still sees them in the more remote reaches of the Fayoum wading about along canals and irrigation ditches apparently living almost entirely on flies. But that is surely an overly simplistic view of the Fayoum Fowl. As all their female ancestors could be traced back to just a few closely-related founders, selection pressures would certainly be expressed via phenotype driven by environmental conditions, such as access to water, and by predation.

Nature Reclaims the Fayoum

Irregardless of the exotic Junglefowl ancestors at the root of its heritage, the Fayoumi had a very long walk along the road of survival to succeed on before it truly came into its own existence. The every movement of these noisy foreign intruders was most assuredly watched by native predators. Species like the Pharaoh's Eagle Owl selected its prey by night, whilst the Egyptian Hawk and Sokar Falcon hunted by day. Every single bird whose plumage failed to conceal it adequately was made all the more vulnerable by that fact. The background surface of every shore and hillock is bright white and burned grey, or ochre and reddish sand, hues no Junglefowl has ever been coloured with.

Its chicks must have been even more vulnerable. Its a marvel that any exotic or foreign species of wildlife much less an ordinary chicken survived all the way into the Late Period when Greeks and Romans held dominion over Egypt and returned Fayoum into a thriving metropolis. But let's not skip ahead as those events were still a thousand years into the future give or take a few measly hundred years. In effect, the Fayoumi Fowl was on its own in the marshes of the Fayoum Basin for nearly a thousand years as a wild species. Until the Greco-Roman period there was no more mention of the domestic fowl and it was Herodotus (?) that mentioned the wild fowl living in the marshes and then, only in passing. They were impossibly wild and served no practical purpose to humankind.

It roosted then as it does now deep in the palm forest at night, which meant that it was obliged to cross wide open spaces to get there. Many of you may wonder why they didn't just stay under the palms to begin with. There is actually very little food to be found beneath palm trees, especially when they grow very closely in dense stands hundreds of acres deep. The palm forest is also home to some of their deadliest enemies. Foremost of these, the Ichneumon , or "Pharaoh's Mouse" which lived in Egypt almost exclusively on the eggs and young of crocodiles and naturally any large birds that came into its forest lair. The Ichneumon is often nocturnal hunting in packs.

The birds would forage beneath the buffalo thorn and acacia for the highly nutritious seeds of these leguminous trees where they were vulnerable to aerial attack by any one of several species of raptor. The grassland tussocks surrounding the Fayoumi Fowl's beloved marshes are home to the Egyptian Lynx, which can jump many yards into the air to capture not just one but two or even three pigeons in one assault. Then there's the Golden Jackal known to snatch prey from the mouths of lions...

Bigawi (Old Egyptian)

Shakshuk

Modern Fayoumi

Dandarawi

There is a whole history of the Fayoumi Fowl that begins a full thousand years after its isolation as a wild bird in the Fayoum Basin.

This is during Greco-Roman times when additional domestic fowl were carried into Egypt from Syria and Persia. These birds were likely very closely related if not identical to the original Tel-Megiddo hen. These tame domestic birds came to live amongst the human settlements along the banks of the lakes of Fayoum. Naturally, this invited the attentions of the wild Bigawi fowl, which interbred freely with their humanized cousins. The modern day Fayoumi Chicken that one buys in hatcheries is generally a descendant of this ancient composite.

There are however, at least three different breeds of Egyptian chickens that deserve mentioning.

The Bigawi is differentiated from the Modern Fayoumi by size, colour and temperament. The Bigawi is a bit smaller and battier than the Fayoumi. Females are a rich chestnut brown with bold black transverse barring. Males are difficult to discern from Modern Fayoumi , though they tend to be darker in the wings with darker and longer tails as well. Both Bigawi and Modern Fayoumi should have dark facial skin and an unusual crow that is easily distinguishable from any other breed of rooster.

The Shakshuk Fayoumi is the common strain of unimproved Fayoumi that one sees in villages throughout the Fayoum and in the cemetery of Old Cairo. They are brightly coloured with vivid yellow legs and ginger hued feathers.

The Dandarawi is of very recent origins created in an agricultural university in Assiut. This breed is analogous with our dual purpose utility breeds. It is a composite of different old African breeds like the Malagasy and European breeds such as the Braekel. A good deal of its genetics come from the Fayoumi fowl as well.

Last edited:

THANK YOU! for the History lesson. Now I want a Fayoumis!

New posts New threads Active threads

-

Latest threads

-

Birds are getting into the run

- Started by Three Stents

- Replies: 0

-

How much egg is too much? Poorly hen.

- Started by BackyardinWales

- Replies: 0

-

-

-

5 Chicken Coop + Run, Recommended Dimensions?

- Started by twinsprouts

- Replies: 1

-

-

Threads with more replies in the last 15 days

-

-

Question of the Day - Friday, February 13th, 2026

- Started by casportpony

- Replies: 93

-

-

-

-

×