THE ORIGIN OF ROSE COMB RHODE ISLAND REDS

BY H. G. DENNIS, in Red Hen Tales.

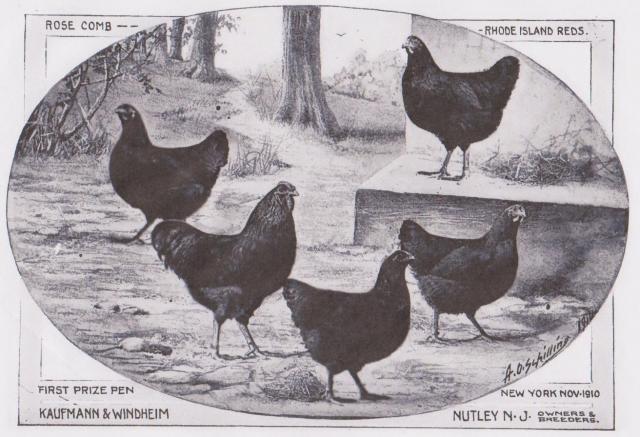

1910

1910

Having seen a number of articles in agricultural and

poultry journals on the origin of the Rhode Island Reds,

and being positive in my belief that I know where the progenitors

of the Rose Comb variety came from, with your

permission will say:

That forty-five years ago to my knowledge, there

could be found on the incoming whaleships, and in the

yards of the sailor boarding houses, and those of the Portuguese

and other foreign residents of that part of New

Bedford, bordering on the water front and known as

Fayal, as well as on a number of farms within a radius

of ten miles of the city, many specimens of red rose comb

fowls that were brought from Java, and the adjacent

islands, by the whale ships, and called by the sailors Red

Javas. The Red Javas would come as near, or nearer, to

meeting

the requirements of the Rhode Island Red standard

than the best Reds today do.

In plumage they would excel the present day Reds.

They were of an even colored rich dark red of a shade

difficult to -describe. Both male and female were dark.

The males had an elegant glossy plumage, and with what

was called in those days a bottle green tail. The females

were more subdued in color and had a black tail. They

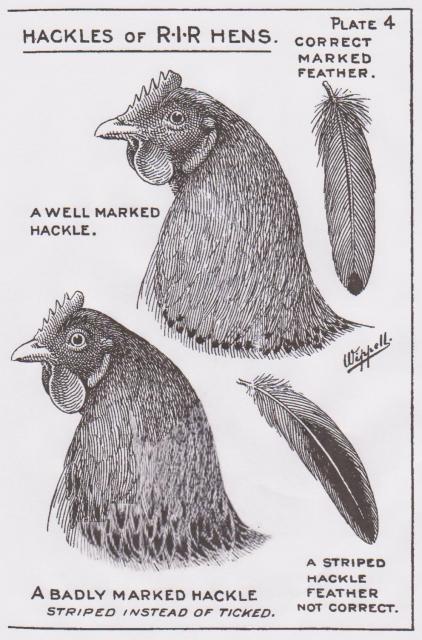

had combs of a fine slant, of medium width terminating

with a spike, comb full and with prominent serrations,

legs of reddish yellow and medium length.

In conformation they were very long on the keel, and

straight on the back. They were very active and great

foragers and layers. In color there were three varieties of

the Javas; red, white and black, all of the same conformation

and characteristics.

That the Javas were a true or distinct breed is my

belief, as many bantams, miniature productions of the large

variety, were to be found in the places that I have before

named.

In company with some schoolmates, we had at one

time about twenty-five specimens of the Red Javas, about

two-thirds of them males. They were obtained in part

from the ships, others were bought from the foreign residents

along the water front. We kept them in a barn

in the center of the city. They soon caused a protest from

the neighbors, and we had to dispose of most of the males.

They were sold to farmers who brought produce to the

city from Little Compton, Adamsville, Westport, Dartmouth,

and to the farmers of the towns to the north and

east of New Bedford.

As many of the officers of the ships came from the

towns above named and westerly along the coast to New

London, and vessels sailed from Westport Point and New

London, it is fair to presume that some of the Javas

found their way to those sections through that channel.

I have kept the Reds many years and would not keep

any other breed. That the Red Javas were the progenitors

as a whole, or in part, of the Rose Comb Reds of today

is my belief, and there is no theory than can be advanced

or argument brought forth,' that would have any effect on

I am not one of those who is willing to say, "Never

mind the origin of the 'Reds' or any other worthy variety

of fowls." I have been breeding poultry for twenty odd

years, and I am always interested in the origin of every

breed. Go back into history with me fifty years, and we

find that, at that time, 1846-1850, different Asiatic breeds

were introduced into this country, especially in neighborhoods

that were near the coast. One variety, the Shanghai

fowl (yellow and white), was introduced just after the

Cochin China, and the two breeds for a time became confused

and "many farmers and poulterers declare, spite of

feathers, or no feathers (on the legs), that their fowls are

Cochin China's or Shanghais, just as they please." At this

time, Bennett, in his poultry book, says: "There are but

few, if any, bona fide Shanghai fowls now for sale." These

Shanghai fowls (Simon pure) were heavily feathered on

the legs, Not so with Cochin China. At this time the

Cochin China's were bred extensively in Southeastern

Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Dr. Alfred Bayless, of

Taunton, Mass., imported in July, 1846, specimens of the

yellow Cochin China's. "The cockerels were generally red."

These were not specimens of what were called the Royal

Cochin China's, as bred by the Queen of England, but

direct importations, "The Royal Cochin China's were one third

larger." The Shanghais were heavily feathered in

the legs; these imported Cochin China's lightly feathered, if

at all. The ship Huntress, in May, 1847, direct from

Cochin China, brought a pair of this variety of fowls, and

Mr. Taylor, in speaking of them, -says: "The imported

cock was a peculiar red and yellowish Dominique, and the

hen a bay or reddish brown;" that the young stock varied

"only in shade of color," Bennett says: "The legs of both,

sexes are of reddish yellow, sometimes, especially in the

cocks, decidedly redmore so than in any other variety."

How many times I have called attention to the red pigment

in a Rhode Island Red cock's legs.

So much, then, for the Red Cochin China cock of fifty

years ago. The sea captains brought home just such specimens

to Little Compton, R. I., but a little later came the

great Malay fowl, with its knotty knob of a comba comb

that even today occasionally is to be seen on the Rhode

Island Reds. The Jersey BluesBucks County and

Boobieswere inferior varieties of Malay. The Great

Malays came from the peninsula of that name at the

southern point of the continent of Asia. They were

spoken of as "serpent headed." Their color was dark

brown or reddish, streaked with yellow; some varieties of

Malays ran more red than others. In Little Compton,

was introduced what was spoken of as the Red Malay.

The Red Cochin China cocks and the Red Malay cocks were

selected, and crossed with the flocks of fowls in Little

Compton, forty and fifty years ago, the same as today.

Later, before the Wyandotte fever, the R. C. Brown Leghorn

was introduced into many flocks in this neighborhood.

Even at the time of the introduction of the Leghorn

blood, the Red fowls were spoken of as Rhode Island Reds.

In a certain section, a section where the Leghorn blood

was not used, . today old settlers speak of their fowls as

Red Malays; in this section ten years ago, the Reds were

all of the single comb variety, whereas, ten or twelve

miles further south were to be found rose combs in

abundance.

Now, Mr. Editor, let me say right here, and I wish

to say it plainly, there practically were no Pea Comb Reds

ten years ago, any more than today. Why should Rhode

Island Red fowls have pea combs? Where is the comb

to come from? It is not the common comb of barnyard

fowl. It is not the comb of any of the varieties that made

the Rhode Island Reds. I should just as much expect to

see the Reds with topknots as with pea combs, and if

Mr. Anybody wants to put topknots on them, go ahead,

only he can't sail in the Rhode Island Red boat this year.

Of course, he can sail in his own boatand who cares.

The Pea Comb, Rocks were once admitted to the Standard,

only to be dropped again. I do not believe the Red Club

will admit Pea Combs only to drop them again. Those

that raise Reds feel differently about Pea Combs from

some of those that raise their pen and ink simply to write

about them.

Chris

BY H. G. DENNIS, in Red Hen Tales.

Having seen a number of articles in agricultural and

poultry journals on the origin of the Rhode Island Reds,

and being positive in my belief that I know where the progenitors

of the Rose Comb variety came from, with your

permission will say:

That forty-five years ago to my knowledge, there

could be found on the incoming whaleships, and in the

yards of the sailor boarding houses, and those of the Portuguese

and other foreign residents of that part of New

Bedford, bordering on the water front and known as

Fayal, as well as on a number of farms within a radius

of ten miles of the city, many specimens of red rose comb

fowls that were brought from Java, and the adjacent

islands, by the whale ships, and called by the sailors Red

Javas. The Red Javas would come as near, or nearer, to

meeting

the requirements of the Rhode Island Red standard

than the best Reds today do.

In plumage they would excel the present day Reds.

They were of an even colored rich dark red of a shade

difficult to -describe. Both male and female were dark.

The males had an elegant glossy plumage, and with what

was called in those days a bottle green tail. The females

were more subdued in color and had a black tail. They

had combs of a fine slant, of medium width terminating

with a spike, comb full and with prominent serrations,

legs of reddish yellow and medium length.

In conformation they were very long on the keel, and

straight on the back. They were very active and great

foragers and layers. In color there were three varieties of

the Javas; red, white and black, all of the same conformation

and characteristics.

That the Javas were a true or distinct breed is my

belief, as many bantams, miniature productions of the large

variety, were to be found in the places that I have before

named.

In company with some schoolmates, we had at one

time about twenty-five specimens of the Red Javas, about

two-thirds of them males. They were obtained in part

from the ships, others were bought from the foreign residents

along the water front. We kept them in a barn

in the center of the city. They soon caused a protest from

the neighbors, and we had to dispose of most of the males.

They were sold to farmers who brought produce to the

city from Little Compton, Adamsville, Westport, Dartmouth,

and to the farmers of the towns to the north and

east of New Bedford.

As many of the officers of the ships came from the

towns above named and westerly along the coast to New

London, and vessels sailed from Westport Point and New

London, it is fair to presume that some of the Javas

found their way to those sections through that channel.

I have kept the Reds many years and would not keep

any other breed. That the Red Javas were the progenitors

as a whole, or in part, of the Rose Comb Reds of today

is my belief, and there is no theory than can be advanced

or argument brought forth,' that would have any effect on

I am not one of those who is willing to say, "Never

mind the origin of the 'Reds' or any other worthy variety

of fowls." I have been breeding poultry for twenty odd

years, and I am always interested in the origin of every

breed. Go back into history with me fifty years, and we

find that, at that time, 1846-1850, different Asiatic breeds

were introduced into this country, especially in neighborhoods

that were near the coast. One variety, the Shanghai

fowl (yellow and white), was introduced just after the

Cochin China, and the two breeds for a time became confused

and "many farmers and poulterers declare, spite of

feathers, or no feathers (on the legs), that their fowls are

Cochin China's or Shanghais, just as they please." At this

time, Bennett, in his poultry book, says: "There are but

few, if any, bona fide Shanghai fowls now for sale." These

Shanghai fowls (Simon pure) were heavily feathered on

the legs, Not so with Cochin China. At this time the

Cochin China's were bred extensively in Southeastern

Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Dr. Alfred Bayless, of

Taunton, Mass., imported in July, 1846, specimens of the

yellow Cochin China's. "The cockerels were generally red."

These were not specimens of what were called the Royal

Cochin China's, as bred by the Queen of England, but

direct importations, "The Royal Cochin China's were one third

larger." The Shanghais were heavily feathered in

the legs; these imported Cochin China's lightly feathered, if

at all. The ship Huntress, in May, 1847, direct from

Cochin China, brought a pair of this variety of fowls, and

Mr. Taylor, in speaking of them, -says: "The imported

cock was a peculiar red and yellowish Dominique, and the

hen a bay or reddish brown;" that the young stock varied

"only in shade of color," Bennett says: "The legs of both,

sexes are of reddish yellow, sometimes, especially in the

cocks, decidedly redmore so than in any other variety."

How many times I have called attention to the red pigment

in a Rhode Island Red cock's legs.

So much, then, for the Red Cochin China cock of fifty

years ago. The sea captains brought home just such specimens

to Little Compton, R. I., but a little later came the

great Malay fowl, with its knotty knob of a comba comb

that even today occasionally is to be seen on the Rhode

Island Reds. The Jersey BluesBucks County and

Boobieswere inferior varieties of Malay. The Great

Malays came from the peninsula of that name at the

southern point of the continent of Asia. They were

spoken of as "serpent headed." Their color was dark

brown or reddish, streaked with yellow; some varieties of

Malays ran more red than others. In Little Compton,

was introduced what was spoken of as the Red Malay.

The Red Cochin China cocks and the Red Malay cocks were

selected, and crossed with the flocks of fowls in Little

Compton, forty and fifty years ago, the same as today.

Later, before the Wyandotte fever, the R. C. Brown Leghorn

was introduced into many flocks in this neighborhood.

Even at the time of the introduction of the Leghorn

blood, the Red fowls were spoken of as Rhode Island Reds.

In a certain section, a section where the Leghorn blood

was not used, . today old settlers speak of their fowls as

Red Malays; in this section ten years ago, the Reds were

all of the single comb variety, whereas, ten or twelve

miles further south were to be found rose combs in

abundance.

Now, Mr. Editor, let me say right here, and I wish

to say it plainly, there practically were no Pea Comb Reds

ten years ago, any more than today. Why should Rhode

Island Red fowls have pea combs? Where is the comb

to come from? It is not the common comb of barnyard

fowl. It is not the comb of any of the varieties that made

the Rhode Island Reds. I should just as much expect to

see the Reds with topknots as with pea combs, and if

Mr. Anybody wants to put topknots on them, go ahead,

only he can't sail in the Rhode Island Red boat this year.

Of course, he can sail in his own boatand who cares.

The Pea Comb, Rocks were once admitted to the Standard,

only to be dropped again. I do not believe the Red Club

will admit Pea Combs only to drop them again. Those

that raise Reds feel differently about Pea Combs from

some of those that raise their pen and ink simply to write

about them.

Chris