The Anatomy and Physiology of the Chicken

When you own a chicken, it is very important to understand the anatomy and physiology of your bird. Anatomy is the science of the structure of animals. Physiology is the science that deals with the functions of the living organism and its parts. Both of these works in tandem with each other to keep your chicken -and all other living organisms- alive and well. When something goes wrong in any part of either the anatomy or the physiology, complications arise -often resulting in the illness or death of the organism.

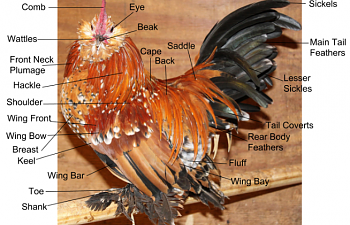

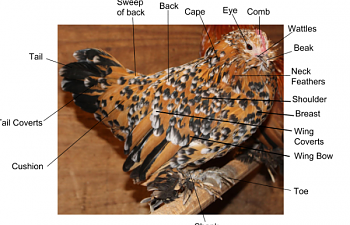

The easiest anatomy of the chicken to assess is the external anatomy. This is the plumage and various appendages that can be seen without any further investigation necessary. This includes the plumage, legs, beak, comb, wattles, eyes, toes, tongue, mouth and skin.

Diagram 1 shows the external anatomy of a mature rooster

Diagram 2 shows the external anatomy of a mature hen

Not only is it important to recognize and know the positions of certain anatomical features, but it is even more important to understand their functions.

Skin, feathers and the beak all serve to protect the bird from external harm. Feathers are dense and specifically shaped to protect the skin from cuts and abrasions as the bird lays down, is in crowded areas or otherwise does the things that chickens do. The beak closes water and airtight to prevent particles from enter the birds trachea as they breathe. When the bird opens its beak, this function is temporarily lost. The skin is the largest organ on any living animal and, as with all species of animal, the skin serves as the first triage for harmful pathogens. When intact, pathogens cannot enter the body through the tissue and good bacteria on the surface of the skin helps to kill off most pathogens. In birds, the skin also acts as a host for feather follicles and an anchor for feather growth.

The comb and wattles serve to regulate the internal temperature of the chicken through the cooling of blood. When a chicken is hot blood rushes into the comb -causing it to turn a brighter red- and the subsequent exposure to cooler air cools the blood in the tiny capillaries that run throughout the comb and wattles. The cooled blood then returns to the inside of the chicken, where it continues to circulate throughout the body. When a chicken is cold its comb becomes paler as the body draws blood from the extremities towards the internal organs to maintain function of critical organs.

The eyes serve as vehicles for vision. The eyelids -of which chickens have three- serve as a level of protection to help prevent harmful pathogens from entering the bloodstream. The outer eyelids clear the eye of debris, while the inner eyelid serves as the 'blinking' mechanism and helps to keep eyes from drying out.

In addition to the aforementioned anatomy, the anatomy of a chicken's wing also has several parts that contribute to the whole. While chickens are generally flightless creatures, they still retain the wing feather anatomy of other birds of flight -just in smaller versions.

Diagram 3 shows the anatomy of the wing plumage

There are seven main parts to the wing, as can be observed above. Each part has a purpose. More information about other feathers on a chicken can be found here.

Primaries are the longest feathers in the wing. They are the outer feathers of the dominant flight feathers and are the strongest of the flight feathers. The primaries grow outwards from the end of each wing.

Secondaries are positioned behind the primaries and are the inner flight feathers. They grow out form the 'forearm' area of the wing. When it comes to soaring and flapping, the secondaries are the feathers that provide the lift.

Primary and secondary coverts aid in streamlining the wing and providing insulation. The marginal Coverts and Alula serve the same function. The Scapulars also known as the tertiary feathers are the innermost flight feathers and are not as important to flight as the primaries and secondaries.

The next page will discuss the digestive system.