I live in North Carolina, the Steamy Southeast of the USA where from June through early September we frequently see 95-95 weather -- 95F and 95% humidity -- and summer nighttime lows may not dip below 70F for weeks. Most chicken-keeping advice is aimed at people in temperate areas with mildly-hot summers and mildly-cold winters, but hot-climate chickens need special consideration just like cold-climate chickens. In fact, chickens tolerate cold much better than they tolerate heat.

(Note: All temperatures given in this article are in Fahrenheit. There is a Fahrenheit to Celsius converter here.)

First thing, climate matters. Dry heat is different than humid heat, in part because the misters and swamp coolers that work so well in hot, arid areas are not only ineffective in humid areas but are actually worse than doing nothing. When the humidity is already 90% adding more water to the air just makes cooling off even harder. It's also easier for birds (or humans), to cope when hot days are accompanied by cool nights that allow them to recover in comfortable temperature than when it never *really* cools off.

Acclimation also matters. For chickens used to cooler weather 85 is distress. For my chickens 85 is a cool day in June, July, or August. A sudden temperature spike is more dangerous than a gradual increase -- a problem I know all too well from when I worked in a factory that had no AC and would get heat illness in May but would be fine at the same temperatures in July.

So, what can you do?

Ventilation is #1

Remember that 1 square foot per adult, standard-sized hen recommended minimum? Throw it out the window. Then throw the windows open wider. In fact, pull the siding off the wall so it's all window.

Seriously, I have found through experience that unless my coop is in deep shade I need at least double or triple the recommended minimums just to keep it under 100F on a 90F day. Roof style matters here. My Little Monitor Coop is OK with only 1.25 times the minimums (not counting the pop door), because the roof style optimizes the chimney effect. The Outdoor brooder can't be kept cool without shade because, despite having up to 26 square feet of ventilation in a 4x8 structure, the flat roof doesn't create any air-FLOW.

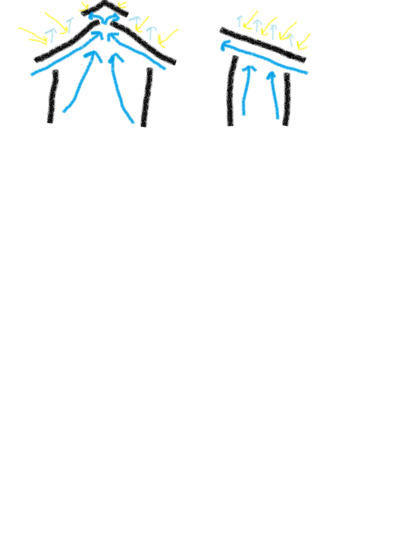

Speaking of airflow you need air to, at the least, flow in from the low point on the roof slope and flow out from the high point.

Soffit and ridge or soffit and gable venting are two common ways to accomplish this. A Monitor or Clerestory roof accomplishes the task even better. Best of all for a truly hot climate, especially in a location where it's hard to provide shade, is an Open Air coop.

But what do I mean with these terms?

The Soffit is the place where a building's roof meets the siding. By replacing the trim boards with wire you can provide excellent ventilation at the low part of the roof. Alternately, you can simply install your siding so that it doesn't quite reach the top of the wall. In both cases it's best to provide a generous roof overhang, which will both shelter the vents from blowing rain, and shade the walls to help keep the coop cooler. For a simple shed roof with only one slope, venting at both the lower and upper soffits will give you excellent airflow on the underside of the roof, removing heat and ammonia and preventing condensation -- the latter being especially important when you use metal roofing.

The ridge is the peak of the roof where two slopes meet. It's critical to let the air out here because heat and ammonia both rise. You can buy manufactured ridge vent by the foot to install instead of the standard cap, or you can construct your roof with a clerestory roof, a monitor roof, or functional cupolas instead. When buying ridge vent be sure to look at how much air it vents per foot then do the math to ensure that it will be sufficient -- remember that you need square feet of venting, not square inches and that in a hot climate meeting the minimums is probably not enough.

Gable vents -- where you do not bring the siding all the way up to the roof peak and use wire instead, can either substitute for or supplement the ridge vent. They should be well-sheltered by generous roof overhangs. Important -- don't be fooled by the apparent easy solution of small metal vents intended to use on sheds. These only move a few square inches of air because the louvers block most of the opening. You need to move square feet of air. A square foot under your gable peak is 1 foot tall and 2 feet wide. I don't have a gable-vented coop of my own to post, but you want this or this, not this or this.

While manufactured ridge vent is the easiest to install in your build, either a clerestory or a monitor is, IMO, superior because it will move considerably more air and, if you live in a hot summer/cold winter area that gets significant snow, it won't get blocked by snow/ice as easily as ridge vent would. For a small coop a functional cupola serves the same purpose but a large coop would require several of them.

Additionally, a clerestory, monitor, or cupola lets light into the center of the coop, which is important in wider coops.

An Open Air coop has at least one wall fully open. A Woods Coop is an open air design intended for northern and temperate areas. For hot climates an Open Air coop best thought of as a roofed wire box for predator protection with a weather shelter at the windward end.

Finally, when it comes to ventilation, height is your friend. First, unless you're in a truly tropical climate, you will have a cool season when you'll want to keep potentially chilling drafts over your birds' heads when they're sitting on the roost. Second, heat rises so a hot-climate coop needs a place for that heat to go.

Here's an article specifically on ventilation: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/repecka-illustrates-coop-ventilation.77659/

Taking Advantage of Terrain

Neuchickenstein, my 16'x16' Open Air coop was built into a north-facing slope at the base of a steeper drop-off (old agricultural terracing). Because the top of the hill is cleared and has houses and buildings in it, the sun's heat creates thermal updrafts there -- pulling a cool breeze out of the woods downslope. We oriented the clerestory roof so as to capture that cool breeze and channel it under the metal roofing. Additionally, a counter-current of cooler air flows down the drop-off against the sheltered wall.

Try carrying a light ribbon around your proposed coop site in different weather conditions to find out how the air flows, especially in your hottest weather, so you can take advantage of natural air movement in addition to the chimney effect that a well-designed roof ventilation system will create.

Shade

There is nothing better that you can do to keep your coop cool than to located it in deep, natural shade provided by sizeable trees. That's how we had the Little Monitor Coop setup on our old property.

But when that's not available, you can use the shade provided by buildings, especially if that shade is cast in the hottest part of the afternoon. Alternately, you can provide shade structures -- which can be as simple as a cheap picnic pavilion.

Other options for shade include tarps strung up on ropes, camo netting, lattice, tall-growing plants such as sunflowers or corn, and vine-covered trellis -- the latter being best planted outside the chickens' actual area so that they don't eat their shade and kill it). Even a patio umbrella can provide a little spot of refuge if well-located.

Nests, Not Ovens

An overheated nestbox with the sun beating on it is, at best, unpleasant. At worst, it can result in spoiled eggs that start to incubate when left in the box all day while you're at work or even a dead hen if she goes broody in it.

Best to locate nests on the shadiest side of the coop and to protect them from direct sun. If this isn't possible, you can vent them and provide protection from, at least, the worst sun of the day. I had to put Neuchickenstein's nests on the west side but I protected them by putting them in the shady coop interior. They also have plenty of airflow because neither the dividers nor the anti-roost board touch the wall.

"Outboard" nests can have wire venting installed at the top on the sides under a roof overhang and top-hinged models can be propped open slightly if the coop is within a predator-proof enclosure.

Let Them Dig!

One way that chickens manage their own temperature in hot weather is by digging into the ground to find the cooler layers beneath the surface. This isn't just dustbathing, it's deliberately creating a comfortable resting place. They pick a shady, possibly moist spot, scrape out a nice bowl, and settle in to rest during the hottest part of the day.

Here are some photos from last summer, with the adult hens in the best spot and the young pullets in their own, separate area.

The Ladies stood up when I approached to see if I had any treats. Because of this, I tend to avoid approaching the coop when it's blistering hot in mid-afternoon because I want the chickens to be able to stay cool and not get all hyper and excited.

WATER!

It should go without saying that chickens, like any other animal coping with hot weather, need an abundant supply of, preferably cool, fresh water.

If possible, keep the waterer in the shade. Some people add ice routinely. I wouldn't do that unless temperatures were well above the norms for my area because I think that they are likely to drink more cool water than icy-cold water -- if only because chickens don't like change and over avoid things that are unfamiliar. If I were to put ice in the water I'd only put it in one of them (I always have at least 2 waterers available at all times in case one is knocked over).

It's important to be vigilant about algae and soiling in hot weather when microorganisms grow rapidly.

Feed?

Some people believe that certain foods, particularly corn, are "heating" and thus recommend to avoid them in hot weather. ALL digestive processes create heat regardless of what's being digested. I don't change my chickens' feed based on weather -- keeping a feeder full of their usual all-flock pellets/crumble at all times. They do get more watery treats such as watermelon rinds, cantaloupe guts, and the good parts of bad tomatoes in the summer but only because we're eating more of that stuff ourselves and thus have more scraps available.

As a matter of principle, I don't feed people food to chickens so I don't give them frozen peas, frozen blueberries, etc. Some people do. However, if we were having temperatures well above our norm where I was considering ice in the water I might also freeze the scraps I was already planning on giving them.

Special Measures

What about electrolytes, water for wading, wetting the run, swamp coolers/misters, fans, and such things?

These can be useful depending on the precise circumstances. I like to give electrolytes once a week during weather over 90F, but ALWAYS in a separate waterer and ALWAYS with plain water available. I have no proof that it helps, but I don't think it can hurt unless the chickens aren't given the plain water option and dehydrate because they rejected the weird-tasting stuff. Imagine if you were given nothing to drink but a Gatorade flavor you don't like with no options.

I have not provided water for wading on a routine basis. Again, it's something I might consider when temperatures are well above our norms. I have wetted a shady portion of the run both incidentally when watering nearby hanging plants and intentionally during dry spells. I don't wet ALL the run, just a portion -- figuring that they will choose what they like best. I figure that chickens know how to be chickens better than I know how to be a chicken so I like to give them options.

Swamp coolers and misters are reported to be VERY useful in arid places where temperatures climb but the humidity remains low. My high temperatures are almost always accompanied by equally high humidity levels so evaporative cooling is largely ineffective here.

I would consider setting up a fan to be strictly an emergency measure, especially inside a chicken coop. I am a strong believer in the superiority of passive ventilation that neither presents a risk of fire nor fails when the electric goes out -- as it so often does in the middle of a blistering-hot afternoon when the power drain from everyone's AC overloads transformers. IF you are going to use a fan it is important to keep the risk of an electrical fire in mind, preferably using a unit that is designed and rated for barn use or, at least, to rig it to blow in rather than out as shown in this build: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/window-fan-mount.75608/

This article includes a lot of information about these special measures you might want to either incorporate into your routine OR use during a heat emergency: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/aarts-extreme-weather-spiel.75893/

Breed Selection

While most common backyard breeds are widely adapted to both heat and cold, there is no getting around the fact that some breeds cope better with extreme temperatures. Any clean-legged bird with a large, single comb is likely to do well, and the Mediterranean breeds most of all. However there are exceptions, most notably Brahmas, who are weirdly heat-tolerant (at least up to a point), despite their thick feathers, feathered feet, and pea combs.

I personally have avoided chickens specifically bred for cold tolerance, such as Buckeyes and Chantecleres, and have been cautious about Wyandottes and Orpingtons. As you can tell from reading this, I'm rather low-input in my heat management -- preferring to set up the overall conditions and not do too much daily micromanagement -- especially because I'm not always home to do such things and can't have chickens who require intensive care.

Another measure I've taken is to get most of my birds from southern-based hatcheries, such as Ideal Hatchery in Texas, on the theory that their breeding flocks are automatically pre-selected for heat-tolerance.

Experience and experimentation will show what birds do best in your particular climate under your particular management system.

(Note: All temperatures given in this article are in Fahrenheit. There is a Fahrenheit to Celsius converter here.)

First thing, climate matters. Dry heat is different than humid heat, in part because the misters and swamp coolers that work so well in hot, arid areas are not only ineffective in humid areas but are actually worse than doing nothing. When the humidity is already 90% adding more water to the air just makes cooling off even harder. It's also easier for birds (or humans), to cope when hot days are accompanied by cool nights that allow them to recover in comfortable temperature than when it never *really* cools off.

Acclimation also matters. For chickens used to cooler weather 85 is distress. For my chickens 85 is a cool day in June, July, or August. A sudden temperature spike is more dangerous than a gradual increase -- a problem I know all too well from when I worked in a factory that had no AC and would get heat illness in May but would be fine at the same temperatures in July.

So, what can you do?

Ventilation is #1

Remember that 1 square foot per adult, standard-sized hen recommended minimum? Throw it out the window. Then throw the windows open wider. In fact, pull the siding off the wall so it's all window.

Seriously, I have found through experience that unless my coop is in deep shade I need at least double or triple the recommended minimums just to keep it under 100F on a 90F day. Roof style matters here. My Little Monitor Coop is OK with only 1.25 times the minimums (not counting the pop door), because the roof style optimizes the chimney effect. The Outdoor brooder can't be kept cool without shade because, despite having up to 26 square feet of ventilation in a 4x8 structure, the flat roof doesn't create any air-FLOW.

Speaking of airflow you need air to, at the least, flow in from the low point on the roof slope and flow out from the high point.

Soffit and ridge or soffit and gable venting are two common ways to accomplish this. A Monitor or Clerestory roof accomplishes the task even better. Best of all for a truly hot climate, especially in a location where it's hard to provide shade, is an Open Air coop.

But what do I mean with these terms?

The Soffit is the place where a building's roof meets the siding. By replacing the trim boards with wire you can provide excellent ventilation at the low part of the roof. Alternately, you can simply install your siding so that it doesn't quite reach the top of the wall. In both cases it's best to provide a generous roof overhang, which will both shelter the vents from blowing rain, and shade the walls to help keep the coop cooler. For a simple shed roof with only one slope, venting at both the lower and upper soffits will give you excellent airflow on the underside of the roof, removing heat and ammonia and preventing condensation -- the latter being especially important when you use metal roofing.

The ridge is the peak of the roof where two slopes meet. It's critical to let the air out here because heat and ammonia both rise. You can buy manufactured ridge vent by the foot to install instead of the standard cap, or you can construct your roof with a clerestory roof, a monitor roof, or functional cupolas instead. When buying ridge vent be sure to look at how much air it vents per foot then do the math to ensure that it will be sufficient -- remember that you need square feet of venting, not square inches and that in a hot climate meeting the minimums is probably not enough.

Gable vents -- where you do not bring the siding all the way up to the roof peak and use wire instead, can either substitute for or supplement the ridge vent. They should be well-sheltered by generous roof overhangs. Important -- don't be fooled by the apparent easy solution of small metal vents intended to use on sheds. These only move a few square inches of air because the louvers block most of the opening. You need to move square feet of air. A square foot under your gable peak is 1 foot tall and 2 feet wide. I don't have a gable-vented coop of my own to post, but you want this or this, not this or this.

While manufactured ridge vent is the easiest to install in your build, either a clerestory or a monitor is, IMO, superior because it will move considerably more air and, if you live in a hot summer/cold winter area that gets significant snow, it won't get blocked by snow/ice as easily as ridge vent would. For a small coop a functional cupola serves the same purpose but a large coop would require several of them.

Additionally, a clerestory, monitor, or cupola lets light into the center of the coop, which is important in wider coops.

An Open Air coop has at least one wall fully open. A Woods Coop is an open air design intended for northern and temperate areas. For hot climates an Open Air coop best thought of as a roofed wire box for predator protection with a weather shelter at the windward end.

Finally, when it comes to ventilation, height is your friend. First, unless you're in a truly tropical climate, you will have a cool season when you'll want to keep potentially chilling drafts over your birds' heads when they're sitting on the roost. Second, heat rises so a hot-climate coop needs a place for that heat to go.

Here's an article specifically on ventilation: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/repecka-illustrates-coop-ventilation.77659/

Taking Advantage of Terrain

Neuchickenstein, my 16'x16' Open Air coop was built into a north-facing slope at the base of a steeper drop-off (old agricultural terracing). Because the top of the hill is cleared and has houses and buildings in it, the sun's heat creates thermal updrafts there -- pulling a cool breeze out of the woods downslope. We oriented the clerestory roof so as to capture that cool breeze and channel it under the metal roofing. Additionally, a counter-current of cooler air flows down the drop-off against the sheltered wall.

Try carrying a light ribbon around your proposed coop site in different weather conditions to find out how the air flows, especially in your hottest weather, so you can take advantage of natural air movement in addition to the chimney effect that a well-designed roof ventilation system will create.

Shade

There is nothing better that you can do to keep your coop cool than to located it in deep, natural shade provided by sizeable trees. That's how we had the Little Monitor Coop setup on our old property.

But when that's not available, you can use the shade provided by buildings, especially if that shade is cast in the hottest part of the afternoon. Alternately, you can provide shade structures -- which can be as simple as a cheap picnic pavilion.

Other options for shade include tarps strung up on ropes, camo netting, lattice, tall-growing plants such as sunflowers or corn, and vine-covered trellis -- the latter being best planted outside the chickens' actual area so that they don't eat their shade and kill it). Even a patio umbrella can provide a little spot of refuge if well-located.

Nests, Not Ovens

An overheated nestbox with the sun beating on it is, at best, unpleasant. At worst, it can result in spoiled eggs that start to incubate when left in the box all day while you're at work or even a dead hen if she goes broody in it.

Best to locate nests on the shadiest side of the coop and to protect them from direct sun. If this isn't possible, you can vent them and provide protection from, at least, the worst sun of the day. I had to put Neuchickenstein's nests on the west side but I protected them by putting them in the shady coop interior. They also have plenty of airflow because neither the dividers nor the anti-roost board touch the wall.

"Outboard" nests can have wire venting installed at the top on the sides under a roof overhang and top-hinged models can be propped open slightly if the coop is within a predator-proof enclosure.

Let Them Dig!

One way that chickens manage their own temperature in hot weather is by digging into the ground to find the cooler layers beneath the surface. This isn't just dustbathing, it's deliberately creating a comfortable resting place. They pick a shady, possibly moist spot, scrape out a nice bowl, and settle in to rest during the hottest part of the day.

Here are some photos from last summer, with the adult hens in the best spot and the young pullets in their own, separate area.

The Ladies stood up when I approached to see if I had any treats. Because of this, I tend to avoid approaching the coop when it's blistering hot in mid-afternoon because I want the chickens to be able to stay cool and not get all hyper and excited.

WATER!

It should go without saying that chickens, like any other animal coping with hot weather, need an abundant supply of, preferably cool, fresh water.

If possible, keep the waterer in the shade. Some people add ice routinely. I wouldn't do that unless temperatures were well above the norms for my area because I think that they are likely to drink more cool water than icy-cold water -- if only because chickens don't like change and over avoid things that are unfamiliar. If I were to put ice in the water I'd only put it in one of them (I always have at least 2 waterers available at all times in case one is knocked over).

It's important to be vigilant about algae and soiling in hot weather when microorganisms grow rapidly.

Feed?

Some people believe that certain foods, particularly corn, are "heating" and thus recommend to avoid them in hot weather. ALL digestive processes create heat regardless of what's being digested. I don't change my chickens' feed based on weather -- keeping a feeder full of their usual all-flock pellets/crumble at all times. They do get more watery treats such as watermelon rinds, cantaloupe guts, and the good parts of bad tomatoes in the summer but only because we're eating more of that stuff ourselves and thus have more scraps available.

As a matter of principle, I don't feed people food to chickens so I don't give them frozen peas, frozen blueberries, etc. Some people do. However, if we were having temperatures well above our norm where I was considering ice in the water I might also freeze the scraps I was already planning on giving them.

Special Measures

What about electrolytes, water for wading, wetting the run, swamp coolers/misters, fans, and such things?

These can be useful depending on the precise circumstances. I like to give electrolytes once a week during weather over 90F, but ALWAYS in a separate waterer and ALWAYS with plain water available. I have no proof that it helps, but I don't think it can hurt unless the chickens aren't given the plain water option and dehydrate because they rejected the weird-tasting stuff. Imagine if you were given nothing to drink but a Gatorade flavor you don't like with no options.

I have not provided water for wading on a routine basis. Again, it's something I might consider when temperatures are well above our norms. I have wetted a shady portion of the run both incidentally when watering nearby hanging plants and intentionally during dry spells. I don't wet ALL the run, just a portion -- figuring that they will choose what they like best. I figure that chickens know how to be chickens better than I know how to be a chicken so I like to give them options.

Swamp coolers and misters are reported to be VERY useful in arid places where temperatures climb but the humidity remains low. My high temperatures are almost always accompanied by equally high humidity levels so evaporative cooling is largely ineffective here.

I would consider setting up a fan to be strictly an emergency measure, especially inside a chicken coop. I am a strong believer in the superiority of passive ventilation that neither presents a risk of fire nor fails when the electric goes out -- as it so often does in the middle of a blistering-hot afternoon when the power drain from everyone's AC overloads transformers. IF you are going to use a fan it is important to keep the risk of an electrical fire in mind, preferably using a unit that is designed and rated for barn use or, at least, to rig it to blow in rather than out as shown in this build: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/window-fan-mount.75608/

This article includes a lot of information about these special measures you might want to either incorporate into your routine OR use during a heat emergency: https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/aarts-extreme-weather-spiel.75893/

Breed Selection

While most common backyard breeds are widely adapted to both heat and cold, there is no getting around the fact that some breeds cope better with extreme temperatures. Any clean-legged bird with a large, single comb is likely to do well, and the Mediterranean breeds most of all. However there are exceptions, most notably Brahmas, who are weirdly heat-tolerant (at least up to a point), despite their thick feathers, feathered feet, and pea combs.

I personally have avoided chickens specifically bred for cold tolerance, such as Buckeyes and Chantecleres, and have been cautious about Wyandottes and Orpingtons. As you can tell from reading this, I'm rather low-input in my heat management -- preferring to set up the overall conditions and not do too much daily micromanagement -- especially because I'm not always home to do such things and can't have chickens who require intensive care.

Another measure I've taken is to get most of my birds from southern-based hatcheries, such as Ideal Hatchery in Texas, on the theory that their breeding flocks are automatically pre-selected for heat-tolerance.

Experience and experimentation will show what birds do best in your particular climate under your particular management system.